Part 4: RISKS · Chapter 11

The Quantum Threat: A Three-Layer Security Analysis

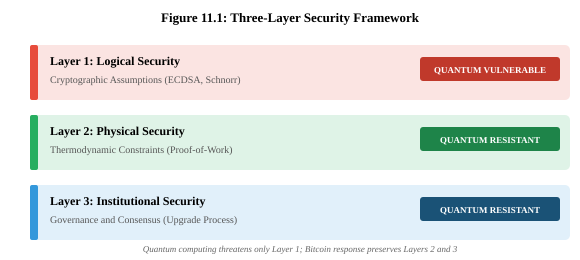

The Three-Layer Security Framework

The preceding chapters established Bitcoin's thermodynamic security as the foundation of the ZeroPoint thesis—security grounded in physics rather than computational assumptions. But what happens when computational assumptions themselves come under attack? Quantum computing poses precisely this challenge, threatening the cryptographic primitives upon which digital signatures depend. This chapter analyzes the quantum threat through a three-layer framework that clarifies both its scope and its limits.

Bitcoin's security architecture can be understood through three distinct layers, each providing different guarantees against different threat categories. This framework clarifies why quantum computing, while presenting genuine challenges, threatens only one layer while leaving the others—including Bitcoin's most fundamental security properties—intact.

Layer 1: Logical Security encompasses cryptographic assumptions—the mathematical hardness problems underlying digital signatures and key derivation. Bitcoin currently relies on the elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem (ECDLP) over secp256k1 for both ECDSA and Schnorr signatures.[11.20] This layer faces existential quantum threat from Shor's algorithm,[11.2] which solves ECDLP in polynomial time.

Layer 2: Physical Security derives from thermodynamic constraints. Bitcoin's proof-of-work mechanism requires irreversible energy expenditure—verified cryptographically rather than through trusted intermediaries. This creates what we term the ZeroPoint property: security grounded in physics rather than computational assumptions. Critically, no quantum computer can violate thermodynamics. Grover's algorithm provides only quadratic speedup for mining (insufficient for practical advantage), and the fundamental requirement of energy expenditure remains inviolate regardless of computational architecture.[11.1, 11.7]

Layer 3: Institutional Security encompasses governance and consensus mechanisms. Bitcoin's demonstrated ability to implement protocol changes—SegWit (2017), Taproot (2021)—provides a proven template for quantum-resistant transitions.[11.8] This layer benefits from Bitcoin's decentralized governance: no single entity can prevent necessary upgrades, while the requirement for broad consensus ensures changes preserve network integrity.

The quantum threat, properly understood, is a Layer 1 challenge requiring Layer 1 solutions. Bitcoin's response—upgrading cryptographic primitives to post-quantum alternatives—preserves Layers 2 and 3 entirely. The thermodynamic anchor that provides unforgeable costliness remains intact. The governance mechanisms that enable orderly transitions remain operational. This framing transforms quantum preparedness from existential crisis to manageable upgrade.

The Quantum Threat: Scope and Timeline

Current State of Quantum Computing

Despite remarkable progress, a substantial gap remains between current quantum capabilities and those required to threaten Bitcoin. Google's Willow processor (105 qubits) demonstrated error correction below threshold in December 2024,[11.4] while IBM's Condor reached 1,121 physical qubits.[11.5] However, breaking secp256k1 requires approximately 2,500 logical qubits with error rates orders of magnitude below current achievements—implying millions of physical qubits with present error correction overhead.[11.9]

Expert assessments converge on 2030-2040 for cryptographically relevant quantum computers (CRQCs), with the Global Risk Institute finding approximately 50% probability by 2035.[11.6] Scott Aaronson, a quantum computing researcher historically skeptical of near-term threats to cryptography, shifted his assessment in September 2024, stating that the possibility of quantum computers breaking current encryption within 5-10 years is now credible enough that "I would now tell you to worry about this."[11.19] Government planning reflects similar timelines: NSA's CNSA 2.0 mandates migration by 2033-2035,[11.10] while Executive Order 14144 strengthened federal quantum preparedness requirements.[11.24]

Table 11.1: Expert CRQC Timeline Assessments

Source | Timeline | Confidence Level |

Global Risk Institute Survey | ~2035 | 50% probability |

NSA CNSA 2.0 | By 2035 | Mandate deadline |

UK NCSC | By 2035 | Planning guidance |

IBM Roadmap | 2033+ | 1,000+ logical qubits |

Conservative Estimate* | 2040+ | Slower progress assumed |

*Author's estimate based on historical progress rates and engineering challenges

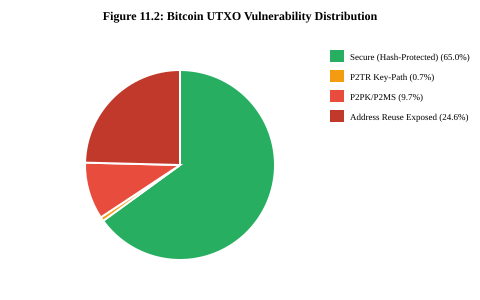

Vulnerability Profile

Bitcoin's UTXO set contains varying degrees of quantum vulnerability. Long-range attacks target outputs with already-exposed public keys, providing unlimited time for quantum computation. Short-range attacks target the broadcast-to-confirmation window when spending reveals public keys—viability depends on CRQC speed (current estimates: hours to days).[11.1]

The most vulnerable category is P2PK outputs, which directly expose the public key in the output script. These represent only 0.025% of UTXOs but hold 8.68% of total value—approximately 1.72 million BTC. The majority are Satoshi-era coinbase outputs, likely permanently inaccessible. P2TR key-path outputs also expose public keys, representing 32.5% of UTXOs but only 0.74% of value. Address-reused UTXOs present a distinct risk: when an address is reused after spending, the prior transaction exposes the public key, transforming otherwise protected outputs into long-range vulnerable targets. This category encompasses 15-20% of supply and is particularly common among exchanges and institutional custodians.[11.1, 11.21]

Critical insight: hash-protected addresses (P2PKH, P2SH, P2WPKH, P2WSH—representing ~65% of value) remain secure against long-range attacks until spending. Grover's algorithm reduces SHA-256 security from 2256 to 2128 operations—still astronomically large. Hash functions are not broken by quantum computing in any practical sense.[11.7]

Table 11.2: Bitcoin Script Type Vulnerability Classification

Script Type | UTXO % | BTC % | Vulnerability Status |

P2PK | 0.025% | 8.68% | Long-range (exposed) |

P2TR (key-path) | 32.5% | 0.74% | Long-range (exposed) |

P2PKH/P2SH/P2WPKH/P2WSH | 66.4% | 90.6% | Short-range only* |

Address-reused† | ~15-20% | ~15-20% | Long-range (exposed) |

*Becomes long-range vulnerable if address reused after spending. †Address-reused is a subset of other categories, not additive.

Post-Quantum Cryptographic Solutions

The Defensive Toolkit

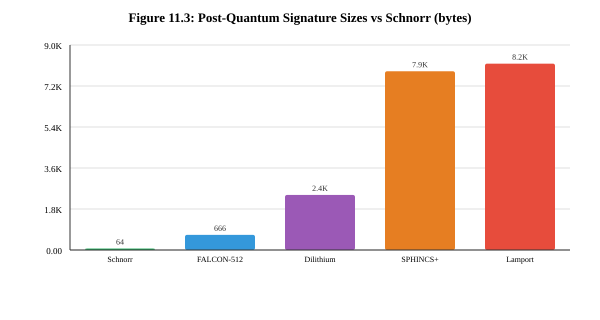

Post-quantum cryptography encompasses mathematical approaches believed resistant to quantum attack. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) finalized standards in 2024-2025:[11.3] FIPS 204 (ML-DSA/Dilithium) for signatures, FIPS 205 (SLH-DSA/SPHINCS+) for stateless hash-based signatures, and FIPS 206 (FN-DSA/FALCON) draft expected 2025.

Hash-based signatures (Lamport, SPHINCS+) derive security from hash function properties—the longest track record, with Lamport signatures predating RSA.[11.14] Lattice-based signatures (Dilithium, FALCON) offer balanced performance with moderate sizes.[11.16] Tradeoff: PQC signatures are substantially larger than classical—SPHINCS+ at 7,856 bytes versus Schnorr at 64 bytes.[11.15]

Bitcoin-Specific Proposals

BIP-360 (P2QRH)—Hunter Beast's comprehensive proposal introduces SegWit v3 outputs ("bc1r" addresses) with hash-protected public keys and hybrid classical/PQC signatures supporting multiple NIST algorithms.[11.12] BIP-347 (OP_CAT)—Heilman and Sabouri propose reintroducing OP_CAT to enable Lamport signature construction within Script, requiring two soft forks.[11.13] STARK Aggregation—Heilman's proposal to compress PQC signatures using zero-knowledge proofs could increase throughput by an order of magnitude versus non-aggregated PQC.[11.22]

Table 11.3: Bitcoin PQC Proposal Comparison

Proposal | Mechanism | Required Changes | Key Tradeoff |

BIP-360 (P2QRH) | New output type | 1 soft fork | Complexity; multiple schemes |

BIP-347 (OP_CAT) | Lamport via script | 2 soft forks | ~8KB signatures; one-time use |

STARK Aggregation | Proof compression | Significant | Novel security assumptions |

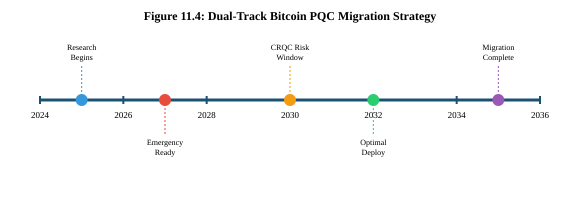

Migration Strategy: Dual-Track Approach

Historical precedent informs realistic timelines. SegWit required approximately 8.5 years from conception to 90% ecosystem adoption; Taproot required approximately 7.5 years from early concepts to activation. However, these timelines reflect the full cycle from research through widespread adoption. Emergency deployment—making quantum-resistant transactions available rather than universally adopted—can proceed much faster. A dual-track strategy addresses both scenarios.

Short-Term Contingency Track (~2 Years)

Minimum viable quantum resistance deployable rapidly if CRQC development accelerates unexpectedly. Components: finalize minimal PQC scheme (3-6 months), Bitcoin Core implementation and review (3-12 months), soft fork activation (6-12 months). This track prioritizes availability over optimization.

Long-Term Comprehensive Track (~7 Years)

Optimal quantum resistance through thorough research and broad consensus: algorithm selection and aggregation research (2-3 years), implementation and testing infrastructure (1-2 years), activation and ecosystem migration (2-4 years). Best case: 5 years with rapid research; worst case: 15 years with governance challenges.[11.1, 11.17]

Migration Mechanisms

Commit-Delay-Reveal (CDR): Three-stage migration enabling movement of vulnerable funds even post-CRQC—commit hash of combined keys, mandatory delay period (proposed 6 months), reveal with quantum-resistant signature.[11.17] QRAMP: Mandatory migration with hard deadline, after which vulnerable UTXOs become unspendable—controversial due to effective confiscation of unmigrated funds. Quantum Canaries: Blockchain bounties locked behind quantum-solvable challenges provide early warning when claimed.

The Burn-Versus-Steal Dilemma

The most contentious aspect of quantum preparedness is not technical but philosophical. Jameson Lopp articulates the burning position: "allowing quantum computers to claim funds = wealth redistribution to quantum arms race winners."[11.18] This treats vulnerability as a protocol bug requiring conservative remediation.

The opposing view, articulated in the Chaincode Labs research, holds that not freezing user funds represents one of Bitcoin's inviolable properties.[11.1] From this perspective, burning represents confiscation regardless of justification. The "do nothing" approach requires no consensus changes, maintaining conservative governance. A middle path—the "hourglass strategy"—rate-limits quantum-vulnerable spends rather than burning or allowing unrestricted theft.

Critically, this debate touches Layer 3 institutional security: Bitcoin's governance must reach consensus on values questions that technical analysis cannot resolve. The demonstrated ability to navigate contentious upgrades (SegWit's User-Activated Soft Fork, Taproot activation) provides precedent, but quantum preparedness may prove more divisive given its implications for property rights.

Preserving the ZeroPoint Property

The three-layer security framework clarifies both the scope and the limits of quantum threat. Quantum computing challenges Layer 1 (cryptographic assumptions) while leaving Layer 2 (physical/thermodynamic security) and Layer 3 (institutional governance) intact. Bitcoin's response—upgrading cryptographic primitives—preserves the fundamental properties that make it uniquely suited for the AI era.

The ZeroPoint thesis, introduced in Chapter 3, holds that Bitcoin's proof-of-work mechanism provides security grounded in physics rather than computational assumptions. You cannot fake energy. No quantum computer can violate thermodynamics. This thermodynamic anchor remains inviolate regardless of quantum progress. A successfully upgraded Bitcoin maintains: zero counterparty risk through cryptographic ownership verified by mathematics; physical security through irreversible energy expenditure; and zero monetary entropy through its fixed supply.

Current expert assessments suggest a 5-10 year window for orderly transition.[11.1, 11.6] The scope of vulnerability (20-50% of supply) is significant but unevenly distributed, with the largest actively managed category (address-reused UTXOs) immediately protectable through operational changes. Multiple technical solutions are under development, with leading cryptographers engaged.

The quantum threat represents perhaps Bitcoin's greatest technical challenge, but also an opportunity to demonstrate decentralized governance resilience. In a world approaching artificial general intelligence, preserving Bitcoin's quantum-resistant security is essential infrastructure for human monetary sovereignty. The window for careful preparation exists today, and the work has already begun.

References

[11.1] Milton, A., & Shikelman, C. (2025). Bitcoin and Quantum Computing: Current Status and Future Directions. Chaincode Labs Research Paper.

[11.2] Shor, P. W. (1994). Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring. Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 124-134.

[11.3] National Institute of Standards and Technology. (2024). Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization. NIST CSRC.

[11.4] Google Quantum AI. (2024). Quantum error correction below the surface code threshold. Nature, 634, 235-241.

[11.5] IBM Research. (2024). IBM Quantum Development Roadmap. IBM Quantum Network.

[11.6] Global Risk Institute. (2024). Quantum Threat Timeline Report 2024. GRI Publications.

[11.7] Grover, L. K. (1996). A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. Proceedings 28th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, 212-219.

[11.8] Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. bitcoin.org.

[11.9] Roetteler, M., et al. (2017). Quantum resource estimates for computing elliptic curve discrete logarithms. ASIACRYPT 2017, 241-270.

[11.10] National Security Agency. (2022). Announcing the Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0. NSA Cybersecurity.

[11.11] UK National Cyber Security Centre. (2024). Next steps in preparing for post-quantum cryptography. NCSC Guidance.

[11.12] Beast, H. (2024). BIP-360: Pay to Quantum Resistant Hash (P2QRH). Bitcoin Improvement Proposal.

[11.13] Heilman, E., & Sabouri, A. (2024). BIP-347: OP_CAT. Bitcoin Improvement Proposal.

[11.14] Lamport, L. (1979). Constructing digital signatures from a one-way function. SRI International CSL-98.

[11.15] Bernstein, D. J., et al. (2017). SPHINCS+: Submission to NIST Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization.

[11.16] Ducas, L., et al. (2018). CRYSTALS-Dilithium: A Lattice-Based Digital Signature Scheme. TCHES, 2018(1), 238-268.

[11.17] Stewart, I., et al. (2018). Committing to quantum resistance: A slow defence for Bitcoin against a fast quantum computing attack. Royal Society Open Science, 5(6).

[11.18] Lopp, J. (2024). On the quantum threat to Bitcoin. lopp.net/bitcoin-information.

[11.19] Aaronson, S. (2024). Quantum computing update. Shtetl-Optimized blog, September 2024.

[11.20] Wuille, P., et al. (2020). BIP-340: Schnorr Signatures for secp256k1. Bitcoin Improvement Proposal.

[11.21] Aggarwal, D., et al. (2018). Quantum attacks on Bitcoin, and how to protect against them. Ledger, 3, 68-90.

[11.22] Ben-Sasson, E., et al. (2018). Scalable, transparent, and post-quantum secure computational integrity. IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive.

[11.23] Mosca, M. (2018). Cybersecurity in an era with quantum computers. IEEE Security & Privacy, 16(5), 38-41.

[11.24] Executive Order 14144. (2025). Strengthening and Promoting Innovation in the Nation's Cybersecurity. Federal Register.

Page of

Coming Soon

This chapter will be available soon.