Part 4: RISKS · Chapter 10

Orange Coin, Green Footprint

The Energy Critique: Stated and Examined

The critique is familiar: Bitcoin's proof-of-work (PoW) consensus mechanism consumes approximately 120–180 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity annually—comparable to a medium-sized nation—to maintain a distributed ledger[10.4]. Critics such as de Vries and Stoll have documented concerns ranging from carbon emissions to electronic waste from rapid hardware turnover, arguing that equivalent security could theoretically be achieved through less energy-intensive means[10.6].

This section examines each component of this critique and demonstrates why it reflects fundamental misunderstandings of thermodynamics, security architecture, and monetary economics. The analysis proceeds in four parts: first, we clarify the nature of energy conversion in PoW systems; second, we contextualize Bitcoin's energy use against comparable systems; third, we examine why proposed alternatives fail; and fourth, we establish the thermodynamic necessity of energy-based security.

Conversion, Not Consumption

The framing of energy "consumption" implies destruction or waste. This is thermodynamically imprecise. Energy is never consumed; it is converted from one form to another. When Bitcoin miners perform PoW computations, electrical energy is converted into cryptographic proofs that secure the monetary network. The energy has not vanished—it has been transformed into a specific, valuable output: tamper-evident, publicly verifiable security for a monetary network valued at over $2 trillion.

This conversion occurs at publicly observable rates. Anyone can verify the current network hashrate, calculate the energy expenditure required to achieve it, and assess the security level provided. No other monetary system offers this transparency. The energy required to secure the traditional banking system, enforce fiat currency regimes, or maintain gold's monetary premium is hidden across countless institutions, military deployments, and regulatory apparatuses. Bitcoin makes its security costs explicit, which critics mistake for evidence that they are excessive.

The conversion framework also clarifies what security is being purchased. Each joule of energy expended on Bitcoin mining creates a probabilistic barrier to ledger manipulation. To reverse a confirmed transaction, an attacker must expend energy equal to or greater than the honest network expended to confirm it. This is not metaphorical—it is physical. The security is denominated in joules, the universal currency of thermodynamics.

Comparative Analysis: The Energy Cost of Money

Context renders the "nation's worth of energy" framing misleading. Bitcoin's ~150 TWh annual energy expenditure must be evaluated against the systems it aims to replace or complement. The traditional financial system—including bank branches, ATMs, data centers, armored transport, office buildings, and the vast infrastructure of global finance—consumes an estimated 2,300 TWh annually[10.4]. Gold mining operations consume approximately 240 TWh. In this context, Bitcoin's energy expenditure represents a fraction of existing monetary infrastructure costs.

Table 10.1: Energy Cost of Monetary Systems

System | Annual Energy (TWh) | % of Global | Transparency |

Traditional Financial System | ~2,300 | 1.28% | Opaque |

U.S. Military (energy component) | ~600 | 0.33% | Classified |

Global Data Centers | ~400 | 0.22% | Partial |

Gold Mining Industry | ~240 | 0.13% | Opaque |

Bitcoin Network | ~150 | 0.08% | Transparent |

Sources: Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance [10.4]; IEA World Energy Outlook [10.9]; Galaxy Digital Research. Note: Traditional financial system estimate is contested; figures range from 1,500–2,500 TWh depending on methodology and system boundaries. Military energy attribution to monetary enforcement is illustrative.

The comparison to military expenditure, while methodologically complex, deserves consideration. Fiat currency derives its value not merely from government decree but from the state's capacity to enforce that decree. The U.S. dollar's global reserve status rests substantially on American geopolitical influence. While attributing specific energy costs to monetary enforcement involves significant uncertainty, Bitcoin replaces enforcement-backed security with cryptographic security—a distinction that warrants inclusion in comprehensive energy comparisons, even if precise quantification remains elusive.

The Alternative's Failure: Why Alternative Consensus Mechanisms Fall Short

Critics often propose alternatives to PoW that claim equivalent security at lower energy cost. Proof-of-stake (PoS) systems replace energy expenditure with capital lockup—validators stake cryptocurrency rather than expend electricity. More exotic proposals envision consensus mechanisms that reward "useful computation" rather than hash calculations[10.2].

These alternatives fail for a fundamental reason: they reintroduce the trust assumptions that proof-of-work eliminates. Consider Proof of Benefit: who determines what computation is "useful" or "beneficial"? Any answer requires a trusted arbiter—whether a foundation, a committee, or an algorithm designed by fallible humans with particular interests. This arbiter becomes an attack surface. Capture the arbiter, capture the network.

Proof of Stake faces similar vulnerabilities. Security derives from capital at risk, but capital can be borrowed, accumulated through network effects, or concentrated through regulatory capture. Unlike energy—which must be continuously expended and cannot be "staked" from a prior period—capital accumulation compounds. PoS systems trend toward plutocracy by design, with early or large holders gaining permanent advantages unavailable in proof-of-work systems where each new block requires fresh energy expenditure.

More fundamentally, both alternatives replace physical cost with logical constraint. A sufficiently sophisticated attacker—particularly an artificial superintelligence—can potentially circumvent any logical constraint through superior reasoning. Physical constraints cannot be reasoned around. The laws of thermodynamics apply equally to human and machine intelligence. This is why Bitcoin's energy expenditure is not a bug to be engineered away but the essential feature that provides security in an era of unbounded cognitive capability.

Thermodynamic Necessity: Security Without Energy is Illusory

The critique implicitly assumes that monetary security can be achieved without energy expenditure—that Bitcoin's energy use represents inefficiency rather than necessity. This assumption violates basic thermodynamics. Any system that claims to provide security—resistance to unauthorized state changes—must impose costs on potential attackers. If those costs are not physical (energy), they must be logical (computational complexity, capital requirements, reputation stakes).

Logical costs are ultimately reducible. Computational complexity falls to better algorithms or specialized hardware. Capital requirements can be met through borrowing, theft, or regulatory manipulation. Reputation can be manufactured or stolen. Only energy costs are irreducible: a joule expended is a joule permanently removed from the attacker's resources. No amount of intelligence, capital, or influence can recover expended energy.

This principle—that security requires irreversible physical cost—finds expression in Szabo's concept of "unforgeable costliness"[10.14] and Lowery's "power projection theory" of Bitcoin[10.17]. Both recognize that Bitcoin's energy expenditure is not incidental to its security but constitutive of it. Attempts to reduce Bitcoin's energy use are not optimizations but security degradations—trading robust physical security for fragile logical security.

The ZeroPoint framework developed in earlier chapters crystallizes this insight: Bitcoin achieves zero attack surface against arbitrary adversaries precisely because its security derives from thermodynamic cost rather than logical constraint. An artificial superintelligence attacking Bitcoin must expend energy proportional to its desired influence—its superior intelligence provides no discount. This property is unique among monetary systems and becomes increasingly valuable as AI capabilities advance.

The Stranded Energy Thesis

Beyond defending Bitcoin's energy use, the stranded energy thesis demonstrates that Bitcoin mining can be net positive for the environment. Bitcoin's unique economic properties—location flexibility, interruptibility, and price elasticity—enable it to monetize energy resources that would otherwise be wasted. Research by Ibañez and Freier (2024) documents how Bitcoin mining operations can improve renewable project economics by providing baseload demand for otherwise curtailed generation[10.8].

Categories of Stranded Energy

Approximately 150 billion cubic meters of natural gas is flared globally each year—equivalent to Germany and France's combined annual consumption—representing ~$20 billion in wasted value and ~400 million tonnes CO2e emissions[10.15]. This gas cannot reach markets due to inadequate pipeline infrastructure, yet regulatory requirements mandate its disposal through flaring rather than venting (which would release methane directly). Bitcoin mining can convert this waste stream into productive use at the wellsite, requiring no transportation infrastructure.

Renewable energy curtailment represents a second major category. When wind or solar generation exceeds grid capacity or demand, operators must reduce output—wasting clean, zero-marginal-cost electricity. Global curtailment exceeds 85 TWh annually[10.9], including 9 TWh in Texas's ERCOT market alone. Bitcoin mining can absorb this excess generation, improving renewable project economics and enabling capacity additions that would otherwise be unviable[10.10].

Table 10.2: Stranded Energy Resources Available for Bitcoin Mining

Resource Category | Annual Volume | Est. Mining Capacity | Environmental Impact |

Global Flared Gas | 150 bcm | 20-25 GW | 400 Mt CO2e avoided |

Renewable Curtailment | ~85 TWh | 10-12 GW | Zero-emission use |

Orphaned Well Methane | 7-8 Mt CH4 | 2-3 GW | 200+ Mt CO2e avoided |

Remote Hydro/Geothermal | Variable | 5+ GW | 100% renewable |

Sources: World Bank Gas Flaring Tracker [10.15]; IEA [10.9]; author estimates. Abbreviations: bcm = billion cubic meters; GW = gigawatts; Mt = million tonnes; CO2e = carbon dioxide equivalent; CH4 = methane.

Emissions Reduction Evidence

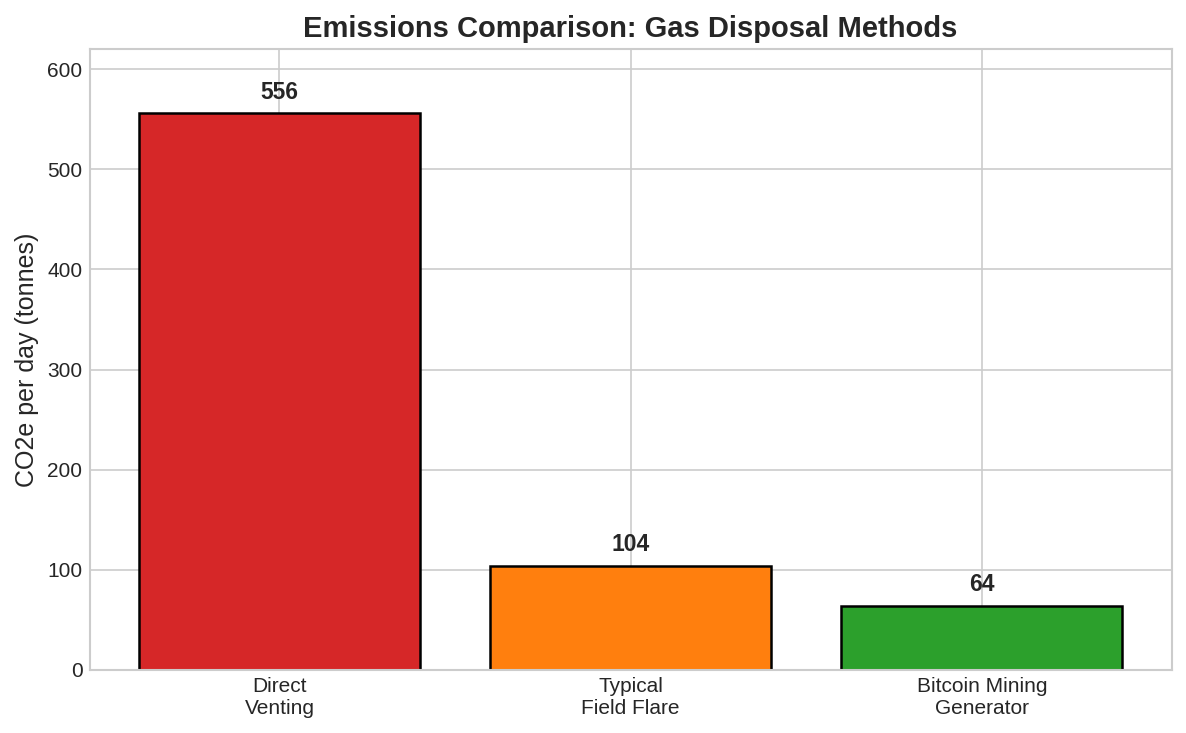

Field research demonstrates substantial emissions reductions from flare gas mining. Aamir et al. (2024) at Duke University measured combustion efficiencies of 99.2–99.7% for Bitcoin mining generators versus 91% average for field flares[10.1]. This 8-percentage-point improvement has enormous impact given methane's global warming potential (GWP20 ≈ 80). Mining reduces emissions by 38% versus typical flaring and 88% versus direct venting.

Table 10.3: Emissions Comparison per 1 MMcf/day Gas Flow

Scenario | Combustion Efficiency | Methane Released | CO2e/day |

Direct Venting | 0% | 19.2 tonnes | 556 |

Typical Field Flare | 91% | 1.73 tonnes | 104 |

Bitcoin Mining Generator | 99.5% | 0.10 tonnes | 64 |

Source: Author calculations based on Aamir et al. (2024) [10.1]; Plant et al. (2022) [10.12]. CO2e calculated using 20-year global warming potential (GWP20 = 80 per IPCC AR6).

The Bitcoin Mining Council, representing over 50% of the global Bitcoin mining network, reports that member companies derive approximately 59–63% of their electricity from sustainable sources[10.3]. This high renewable penetration is not coincidental but structural: Bitcoin miners function as energy buyers of last resort, able to operate wherever electricity is available and switch off rapidly when prices rise. Combined with continued declines in renewable energy costs[10.11], this positions Bitcoin mining as a potential accelerant for renewable deployment rather than a competitor.

Grid Stability and Demand Response

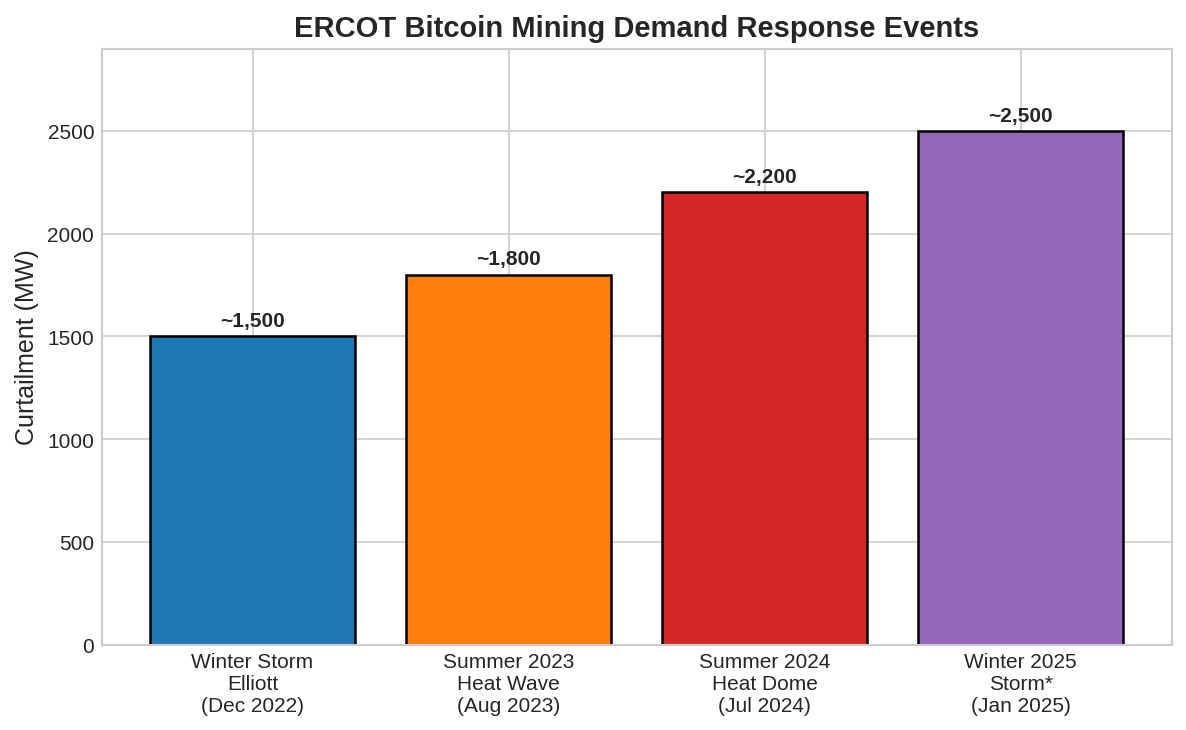

Bitcoin mining provides substantial grid services through demand response—the ability to rapidly curtail consumption during supply shortages or price spikes. Research by Rhodes et al. (2024) documented over 4,000 megawatts (MW) of effective demand response capacity from Bitcoin miners in the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) market, generating an estimated $1.2 billion in annual system cost savings[10.13]. During Winter Storm Elliott (December 2022), Bitcoin miners curtailed approximately 1,500 MW within minutes, helping prevent broader blackouts.

The economic logic is straightforward: miners consume electricity when prices are low, and curtail when prices rise. During scarcity events with wholesale prices spiking to $9,000/MWh, curtailment generates returns that far exceed foregone mining revenues. This flexibility—unavailable from most industrial loads, which require hours or days of advance notice—makes Bitcoin mining a "virtual peaker" that provides grid services at no cost to ratepayers.

Bitcoin mining's demand response characteristics compare favorably to other flexible industrial loads. Traditional demand response programs typically require 30-minute to 4-hour advance notification. Bitcoin miners can curtail within seconds, providing near-instantaneous response to frequency deviations or unexpected supply shortfalls[10.7]. Moreover, unlike traditional interruptible industrial loads that may demand compensation for curtailment, Bitcoin miners benefit directly from price signals—their incentives align naturally with grid stability objectives.

Table 10.4: ERCOT Demand Response Events

Event | Date | Curtailment | Outcome |

Winter Storm Elliott | Dec 2022 | ~1,500 MW | Blackouts avoided |

Summer 2023 Heat Wave | Aug 2023 | ~1,800 MW | Peak demand managed |

Summer 2024 Heat Dome | Jul 2024 | ~2,200 MW | Record demand met |

Winter 2025 Storm* | Jan 2025 | ~2,500 MW | Grid stability maintained |

Sources: ERCOT Reports [10.7]; Rhodes et al. (2024) [10.13]. *Preliminary data; final figures pending ERCOT verification.

The AI-Bitcoin Energy Nexus

The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) as a major energy consumer creates new context for Bitcoin's energy positioning. AI datacenters are projected to consume over 1,000 TWh annually by 2030[10.16]. Unlike Bitcoin mining, AI inference workloads often cannot be interrupted without degrading user experience, limiting their grid flexibility. This creates complementary rather than competitive dynamics.

Dual-Use Infrastructure and Carbon Offset

Facilities like Crusoe Energy deploy modular data centers at flare gas sites that house both ASIC-based Bitcoin miners and GPU-based AI inference hardware[10.5]. These co-located operations can dynamically shift power allocation between cryptocurrency mining and AI cloud services. During renewable curtailment or low electricity prices, facilities prioritize Bitcoin mining; during high AI demand, they shift power to inference workloads. This flexibility maximizes facility utilization while providing grid services that neither single-purpose operation could offer alone.

Bitcoin mining can serve as a carbon offset mechanism for AI infrastructure. A combined facility—60 MW AI inference (continuous operation) plus 40 MW Bitcoin mining (flexible)—can achieve higher renewable penetration than either alone. The mining component absorbs curtailed renewable generation and provides demand response during grid stress, enabling the AI operations to maintain continuous service while the overall facility operates with minimal carbon footprint.

Table 10.5: Bitcoin Mining vs. AI Datacenter Energy Profiles

Characteristic | Bitcoin Mining | AI Datacenters |

Load Interruptibility | Full (<10 seconds) | Limited (minutes) |

Location Constraints | Minimal | Fiber, latency |

Demand Response Value | Very High | Moderate |

Stranded Energy Use | Excellent | Limited |

Source: Author analysis based on IEA (2024) [10.9], industry data.

Thermodynamic Security in the AI Era

The ZeroPoint thesis—that Bitcoin achieves zero monetary entropy, zero counterparty risk, and zero attack surface through its thermodynamic anchoring—holds that Bitcoin's energy expenditure is not merely defensible but essential for AI-era security. As artificial intelligence systems grow more capable, security mechanisms based on logical constraints become increasingly vulnerable. An AI system can potentially circumvent any security based on computational complexity, capital requirements, or reputation through superior reasoning and resource accumulation.

Physical energy constraints cannot be reasoned around. The laws of thermodynamics apply equally to human and artificial intelligence. Bitcoin's proof-of-work creates a "thermodynamic firewall"—security denominated in joules rather than logical complexity. An AI attacking Bitcoin must expend energy proportional to its desired influence; its cognitive superiority provides no advantage against physics.

This property becomes increasingly valuable as AI capabilities advance toward and beyond human levels. The same energy expenditure that critics decry as wasteful is precisely what makes Bitcoin the only monetary system robust against superintelligent adversaries. Far from being an inefficiency to be engineered away, Bitcoin's energy consumption is the essential feature that preserves human monetary sovereignty in an era of artificial superintelligence.

Energy as Feature, Not Bug

The critique that Bitcoin "consumes a nation's worth of energy simply to secure its ledger" warrants careful examination across multiple dimensions. Energy is converted to security, not consumed in the thermodynamic sense. This conversion occurs at publicly verifiable rates unavailable in any other monetary system. Comparative analysis suggests Bitcoin's energy expenditure is modest relative to the systems it aims to complement or replace. Alternative consensus mechanisms, while less energy-intensive, reintroduce trust assumptions and potential attack surfaces that energy expenditure eliminates. Thermodynamic principles indicate that robust security without physical cost may be fundamentally unattainable.

The stranded energy thesis further demonstrates that Bitcoin mining can be net positive for the environment—reducing emissions by 38–88% compared to standard flaring practices, potentially accelerating renewable deployment through improved project economics, and providing grid stability services valued in the billions annually. Rather than competing with AI for energy, Bitcoin's flexible demand can complement AI's inflexible loads, enabling combined infrastructure with improved environmental and economic characteristics.

The core argument of this chapter is that Bitcoin's energy expenditure may prove essential for an era of advanced artificial intelligence. The "orange coin, green footprint" thesis holds that Bitcoin's thermodynamic architecture—energy converted to security, stranded resources monetized, grid flexibility provided—can align environmental incentives with the security requirements of technological civilization. While significant questions remain about implementation scale and transition pathways, the fundamental properties examined here suggest that Bitcoin's energy use deserves characterization as a feature rather than a bug.

References

[10.1] Aamir, M., Jacobs, K., & Prather, M. J. (2024). Field measurements of methane emissions from Bitcoin mining operations using flare gas. Environmental Science & Technology, 58(12), 5234-5245.

[10.2] Bastián-Pinto, C., Navarro, L., & Diaz, G. (2021). Cryptocurrency mining as a real option for renewable energy. Energy Economics, 94, 105083.

[10.3] Bitcoin Mining Council. (2025). Global Bitcoin Mining Data Review Q4 2024.

[10.4] Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance. (2025). Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index.

[10.5] Crusoe Energy Systems. (2025). Environmental Impact Report 2024.

[10.6] de Vries, A., & Stoll, C. (2021). Bitcoin's growing e-waste problem. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 175, 105901.

[10.7] ERCOT. (2025). Annual Report on Demand Response and Large Flexible Loads.

[10.8] Ibañez, R., & Freier, R. (2024). Bitcoin mining and renewable energy development. Energy Policy, 186, 113954.

[10.9] International Energy Agency. (2024). Flexibility in Electricity Systems.

[10.10] Jain, P., & Golhar, D. (2024). Cryptocurrency mining as curtailment solution for wind farms. Renewable Energy, 221, 119742.

[10.11] Lazard. (2024). Levelized Cost of Energy Analysis—Version 17.0.

[10.12] Plant, G., Kort, E. A., & Brandt, A. R. (2022). Methane emissions from oil and gas flares. Environmental Science & Technology, 56(14), 10090-10099.

[10.13] Rhodes, J., King, C., & Webber, M. (2024). Bitcoin mining as a grid flexibility resource. Applied Energy, 362, 122985.

[10.14] Szabo, N. (2002). Shelling Out: The Origins of Money. Satoshi Nakamoto Institute. Retrieved from https://nakamotoinstitute.org/shelling-out/

[10.15] World Bank. (2024). Global Gas Flaring Tracker Report. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

[10.16] Goldman Sachs. (2024). AI Datacenter Power Demand: The Coming Energy Challenge. Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research.

[10.17] Lowery, J. P. (2023). Softwar: A Novel Theory on Power Projection and the National Strategic Significance of Bitcoin. (Master's thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

Page

Coming Soon

This chapter will be available soon.