Part 1: FOUNDATIONS · Chapter 2

Money Is Time and Energy in Abstracted Form

The Fundamental Nature of Money

What is money, fundamentally? This question, deceptively simple in its formulation, has occupied philosophers, economists, and political theorists for millennia. From Aristotle's distinction between natural and unnatural acquisition to Adam Smith's analysis of the division of labor, from Carl Menger's theory of the spontaneous emergence of money to contemporary debates about cryptocurrency, the nature of money remains contested ground.

Strip away the legal definitions, the economic jargon, and the political positioning, and one finds something startlingly elemental: money is human time and energy in abstracted form. This formulation, while seemingly reductive, captures an essential truth that modern monetary theory has largely obscured. When an individual engages in productive labor, they convert their finite allocation of time and their expenditure of physical and cognitive energy into value for others. In exchange, they receive money—a symbolic token representing that expenditure. Money, properly conceived, is supposed to store that time and energy so it can be deployed later: to purchase shelter, to fund retirement, to transfer wealth intergenerationally. Money is the mechanism by which human beings transport value across the temporal dimension.[1]

This chapter develops this thesis through several interconnected arguments. First, we establish the theoretical foundations linking money to time and energy through classical and Austrian economics (Section 2.2). Second, we explore a deeper thermodynamic framework connecting intelligence, entropy, and the creation of monetary order, introducing the concept of 'crystallized intelligence' (Section 2.3). Third, we present empirical evidence on the erosion of purchasing power under fiat monetary systems (Section 2.4). Fourth, we analyze the distributional consequences of monetary expansion through the Cantillon effect (Section 2.5). Fifth, we examine the ethical dimensions of monetary debasement (Section 2.6). Sixth, we consider the civilizational consequences through the lens of time preference (Section 2.7). Finally, we examine how Bitcoin's technological architecture addresses these fundamental problems (Section 2.8) and offer concluding reflections (Section 2.9).

Theoretical Foundations: Money as Stored Labor

Classical Perspectives on Value and Exchange

The relationship between money and labor has deep roots in economic thought. Adam Smith, in The Wealth of Nations (1776), observed that 'the real price of everything, what everything really costs to the man who wants to acquire it, is the toil and trouble of acquiring it.'[2] This insight—that the ultimate measure of value is human effort—establishes the conceptual foundation for understanding money as abstracted labor.

David Ricardo formalized this intuition in his labor theory of value, arguing that the relative value of commodities is determined by the quantity of labor required to produce them.[3] While the marginalist revolution of the 1870s—associated with Jevons, Menger, and Walras—superseded this framework with subjective value theory, the underlying recognition that production requires the sacrifice of time and energy remains foundational to economic analysis.[4]

The Austrian school, particularly through the work of Carl Menger and Ludwig von Mises, refined our understanding of money's emergence and function. Menger (1892) demonstrated that money arises spontaneously from market processes as the most marketable commodity—the good most readily exchangeable for other goods.[5] This 'regression theorem,' later formalized by Mises (1912), shows that money's purchasing power can be traced back through time to the original commodity's non-monetary utility value.[6]

The Thermodynamic Perspective

A more fundamental understanding emerges when we consider money through the lens of thermodynamics. All economic production requires energy transformation. The first law of thermodynamics—the conservation of energy—implies that economic value cannot be created ex nihilo; it must be transformed from existing inputs, primarily human time and energy expenditure.

Human labor, at its most basic level, involves the conversion of metabolic energy (derived from food, which is itself stored solar energy) into useful work. When a carpenter builds a chair, they convert biological energy into kinetic energy, which transforms raw materials into a finished product. The market price of that chair represents, in abstracted form, the energy expenditure required for its production.

Money, in this framework, functions as a claim on energy. When one saves money, one is storing claims on future energy expenditure. When one spends money, one is directing energy flows toward particular productive ends. Sound money preserves these claims across time; debased money dissipates them.[1]

Intelligence as Entropy Reduction: A Deeper Theoretical Framework

The Intelligence-Entropy Relationship

To fully understand why energy expenditure is essential to sound money, we must engage with a more fundamental question: what is the relationship between intelligence, energy, and order? Emad Mostaque, founder of Stability AI and a leading figure in artificial intelligence research, has offered a striking formulation: intelligence functions as 'the universe's engine for creating temporary pockets of order against entropy.'[7] This framing, which draws on information theory and thermodynamics, has profound implications for monetary theory.

The second law of thermodynamics states that entropy—disorder—tends to increase in closed systems over time. Left alone, ordered structures decay into chaos. Yet we observe islands of increasing order throughout the universe: crystals form, life emerges, civilizations arise. How is this possible? The answer lies in energy expenditure. Creating and maintaining order requires the input of energy; the local decrease in entropy is always paid for by a larger increase in entropy elsewhere in the system.[8]

Intelligence, whether biological or artificial, can be understood as a mechanism for directing energy toward the creation of ordered states. A bird builds a nest; a human builds a cathedral; an AI system organizes data into useful patterns. In each case, energy is expended to create structure where none existed before. The more sophisticated the intelligence, the more complex the order it can create—but the fundamental thermodynamic constraint remains: order requires energy.[9]

Money as Ordered Information

This framework illuminates the deep connection between money and energy. Money is not merely a medium of exchange or store of value—it is ordered information. A monetary system is an informational structure that coordinates economic activity across time and space. Like all ordered structures, it requires energy to create and maintain.

Under commodity money systems, this energy requirement was implicit. Gold required mining—the expenditure of enormous human and mechanical energy to extract ordered metal from disordered ore. The scarcity of gold was a function of the energy required to produce it. Paper money backed by gold inherited this thermodynamic anchor through the promise of convertibility.

Pure fiat money severed this connection. When money can be created by central bank ledger entries—without corresponding resource expenditure—the thermodynamic anchor is lost. Fiat money is information without the energy expenditure that creates genuine order. It is, in thermodynamic terms, an attempt to create order without paying the entropy cost. The inevitable result is monetary inflation: the degradation of the informational order that money is supposed to represent.[1]

Proof-of-Work: The Thermodynamic Anchor Restored

Bitcoin's proof-of-work mechanism can now be understood in its proper context: it is the explicit, measurable conversion of energy into monetary order. When a Bitcoin miner expends electricity to solve cryptographic puzzles, they are not 'wasting' energy—they are creating order against entropy. The energy expenditure is the thermodynamic cost of producing genuine monetary scarcity in digital form.[10]

Critics of Bitcoin often characterize this energy expenditure as wasteful or extractive.[7] This criticism fundamentally misunderstands the thermodynamic necessity. In an age of infinite digital replication—where any piece of information can be copied at near-zero cost—how does one create genuine digital scarcity? The answer is energy. Only by tethering digital tokens to real-world energy expenditure can one prevent the unlimited replication that would destroy monetary value.

The energy expenditure is not a bug; it is the essential feature. It is what makes Bitcoin real in a way that fiat currency cannot be. Every bitcoin represents a verified conversion of physical energy into informational order—a token that cannot be counterfeited, duplicated, or inflated away because its creation required irreversible thermodynamic work.[11]

Crystallized Intelligence: A New Framework for Monetary Value

We propose the term 'crystallized intelligence' to describe what proof-of-work creates. Just as a crystal represents atoms organized into a low-entropy, highly ordered lattice structure, a bitcoin represents energy organized into a low-entropy, highly ordered informational structure. The mining process crystallizes raw energy into monetary form—converting undifferentiated electrical power into a specific, verifiable, non-duplicable token of value.

This framing resolves the apparent paradox of digital scarcity. How can something that exists only as information be genuinely scarce? Because its creation requires genuine energy expenditure. The bitcoin is not scarce because of arbitrary decree or network consensus alone—it is scarce because the laws of thermodynamics make it expensive to produce. The proof-of-work algorithm translates physical scarcity (energy) into informational scarcity (bitcoin).[12]

This framework also illuminates why alternative consensus mechanisms represent fundamentally different propositions. Proof-of-stake systems secure networks through existing token holdings rather than ongoing energy expenditure. Proponents argue that proof-of-stake achieves security through economic incentives—validators risk capital loss through slashing if they behave dishonestly. However, this security model remains endogenous to the system: the value at risk is denominated in the token being secured, creating a circularity absent from proof-of-work's exogenous thermodynamic anchor. While proof-of-stake may be more 'efficient' in narrow energy terms, it severs the connection to physical reality that gives proof-of-work its distinctive security properties.[13]

Table 1: The Energy-Money-Intelligence Transformation Framework

Stage | Physical Process | Thermodynamic Function | Monetary Manifestation |

1. Energy Input | Electricity generation | Available work potential | Mining operational cost |

2. Computational Work | Hash calculations | Entropy increase (heat) | Proof-of-work process |

3. Order Creation | Valid block discovery | Local entropy decrease | New bitcoin minted |

4. Crystallization | Blockchain recording | Information preservation | Immutable ownership record |

5. Value Storage | Network consensus | Ordered state maintenance | Store of crystallized energy |

Source: Author's synthesis of thermodynamic, information-theoretic, and economic principles

The theoretical framework developed above suggests that fiat monetary systems, by severing money from thermodynamic reality, should exhibit systematic value degradation over time. The empirical record since 1971—when the last vestige of commodity backing was removed from the international monetary system—provides a natural experiment for testing this hypothesis.

The Empirical Record: Purchasing Power Erosion Under Fiat Money

The Post-1971 Monetary Regime

On August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon announced that the United States would suspend the convertibility of dollars into gold—a measure he characterized as 'temporary.'[14] This decision marked the definitive end of the Bretton Woods system and the beginning of a purely fiat monetary order. The implications of this transition have been profound and far-reaching.

When Nixon severed the dollar's link to gold, he did not merely make a monetary policy decision—he unmoored money from physical reality. In thermodynamic terms, he severed the connection between monetary order and energy expenditure. The gold standard, whatever its limitations, imposed a hard constraint on monetary expansion because gold required energy to produce. The post-1971 system removed this constraint entirely, enabling potentially unlimited monetary expansion at the discretion of monetary authorities—order by decree rather than order through work.[15]

Indicator | 1971 | 2024 | Change |

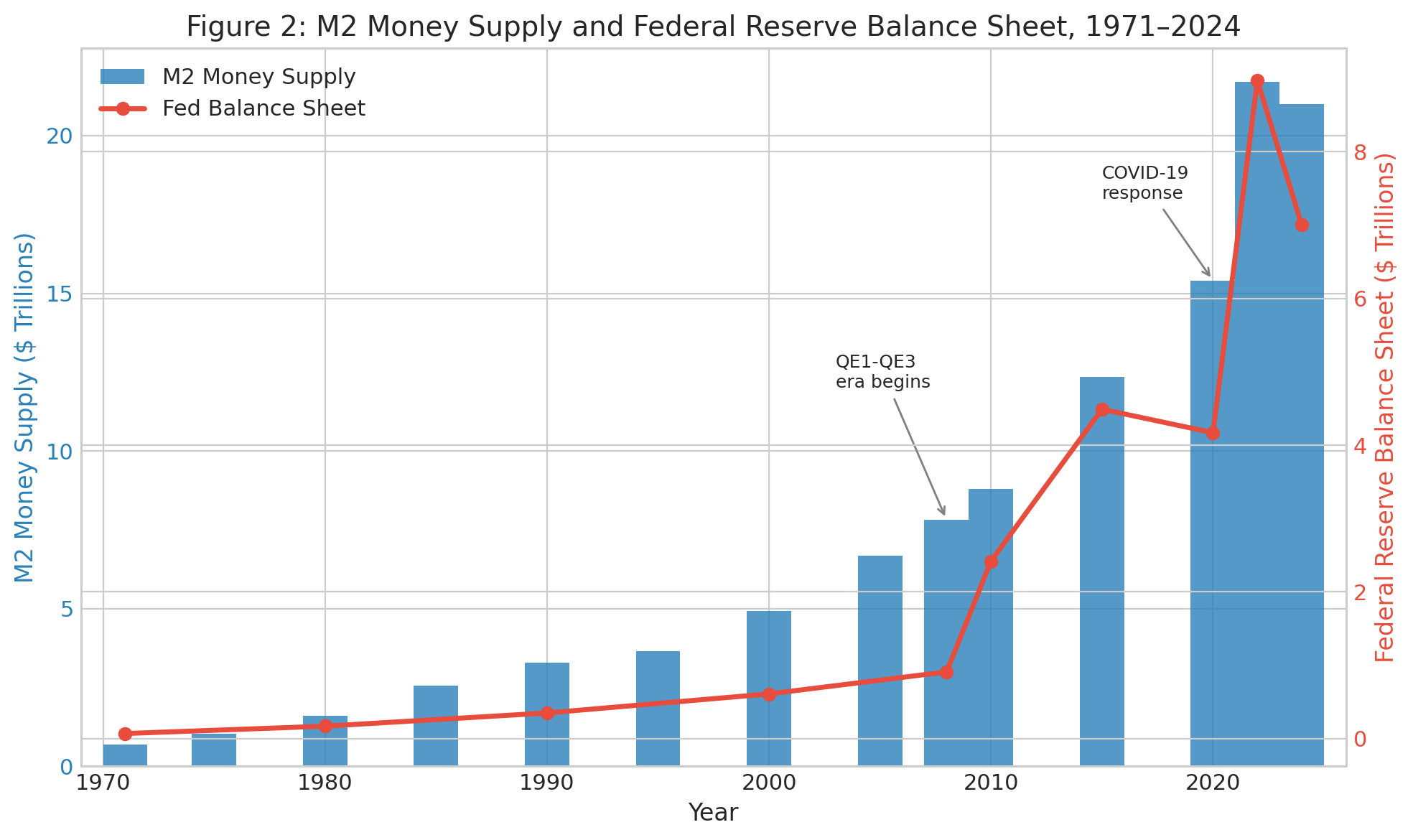

U.S. M2 Money Supply | $0.69T | $21.0T | +2,943% |

Federal Reserve Balance Sheet | $0.07T | $7.0T | +9,900% |

U.S. National Debt | $0.4T | $34.0T | +8,400% |

Global Debt | ~$5T | $315T | +6,200% |

CPI-U Index (1982-84=100) | 40.5 | 314.5 | +677% |

Dollar Purchasing Power | $1.00 | $0.13 | -87% |

Note: Purchasing power calculated using CPI-U (All Urban Consumers). Sources: FRED, BLS, IMF Global Debt Database[16][17][18]

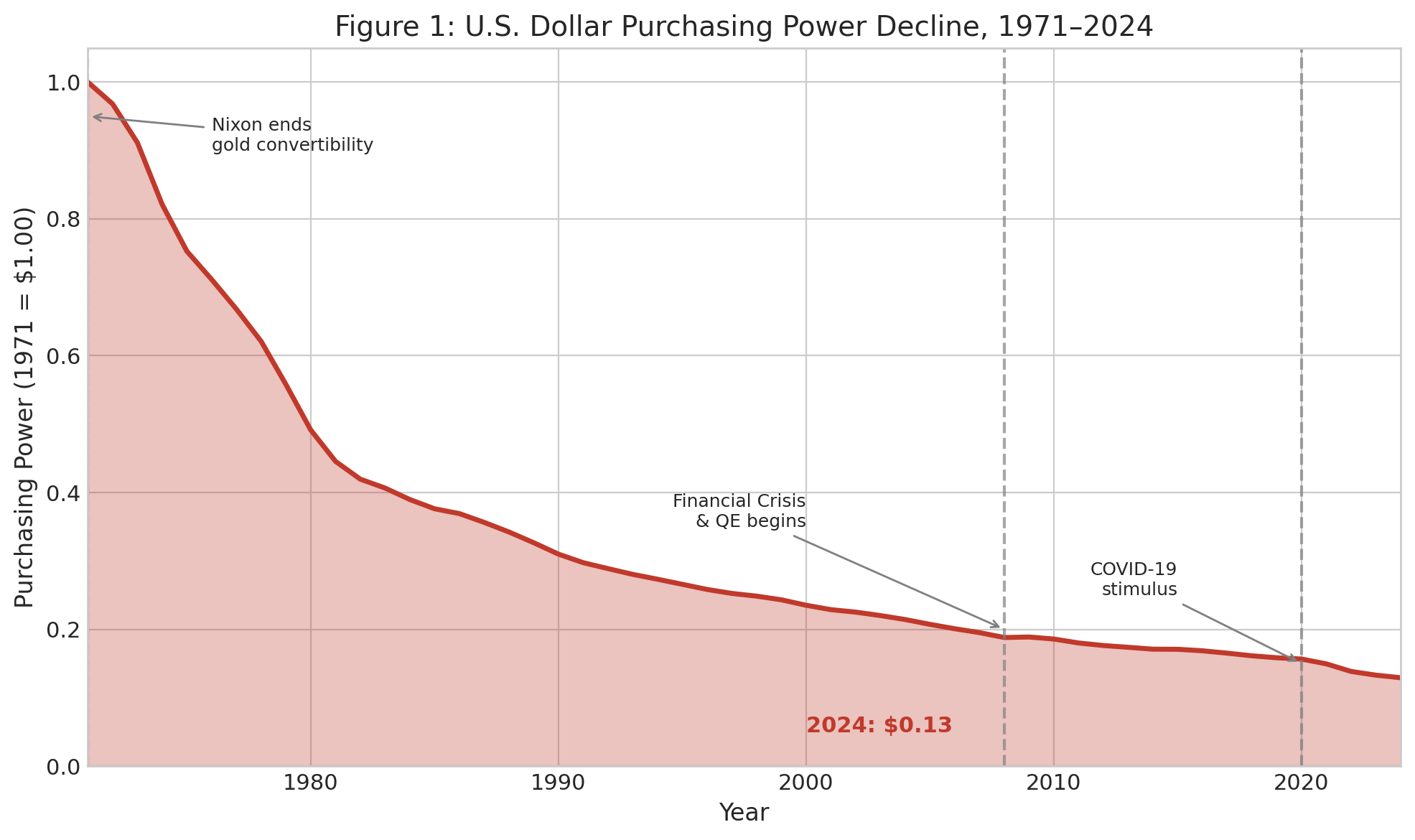

The Mechanics of Purchasing Power Erosion

The data presented in Table 2 and Figures 1-2 reveal a stark reality: the U.S. dollar has lost approximately 87% of its purchasing power since 1971, as measured by the CPI-U index. This erosion is not incidental—it is the predictable consequence of creating monetary 'order' without the corresponding energy expenditure. In thermodynamic terms, fiat expansion represents entropy masquerading as order.[16]

Consider the concrete implications. A worker who earned $10,000 in 1971 and saved that sum in cash would find their purchasing power reduced to approximately $1,300 in today's terms. The time and energy they sacrificed to earn those dollars—the labor, the forgone leisure, the deferred consumption—has been largely diluted through monetary expansion that required no comparable effort to create.

This dynamic explains why inflation is not merely an economic inconvenience but a systematic transfer mechanism. When money is devalued, the saver's accumulated purchasing power is eroded. Every hour worked to earn that money becomes worth less with each passing year. The purchasing power painstakingly accumulated through sacrifice of present consumption is transferred—silently, incrementally—to those who received the newly created money first.[19]

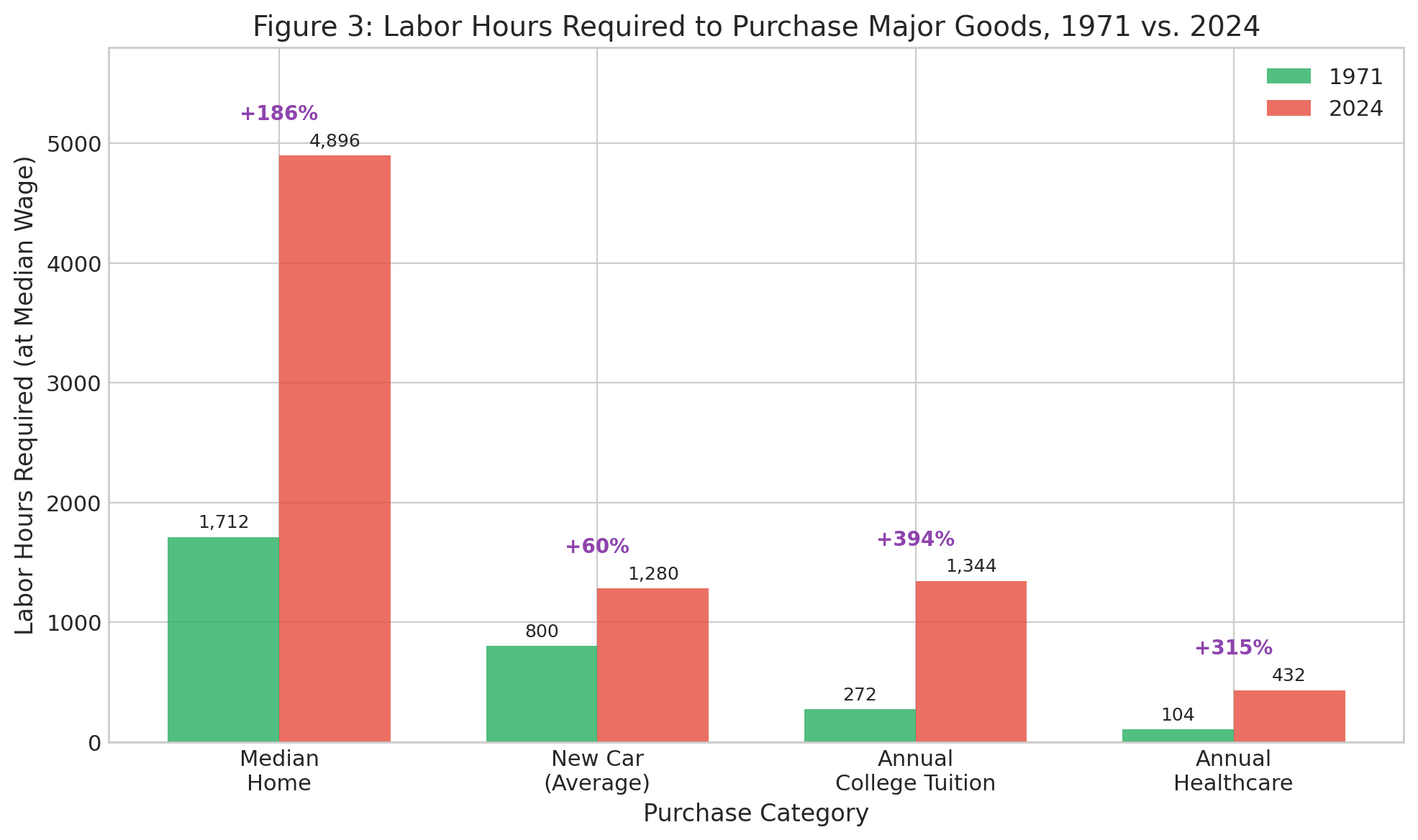

Item | 1971 Hours | 2024 Hours | Change | % Change |

Median Home | 1,712 | 4,896 | +3,184 | +186% |

New Car (Average) | 800 | 1,280 | +480 | +60% |

Annual College Tuition | 272 | 1,344 | +1,072 | +394% |

Annual Healthcare Spending | 104 | 432 | +328 | +315% |

Dozen Eggs | 0.15 | 0.10 | -0.05 | -33% |

Note: Calculations based on median hourly wages for production/nonsupervisory workers and average prices. Sources: BLS, NAR, NADA, College Board[17][20][21]

Table 3 and Figure 3 illustrate the divergent impact of inflation across different categories of goods. While technological advances have reduced the labor cost of some commodities (eggs, basic consumer electronics), assets with inelastic supply—particularly housing and education—have become dramatically more expensive in labor terms. A worker in 2024 must labor nearly three times as many hours to purchase a median home as their counterpart in 1971. This represents a substantial intergenerational transfer of wealth from wage earners to asset holders.[20]

The Cantillon Effect: Distributional Consequences of Monetary Expansion

Theoretical Framework

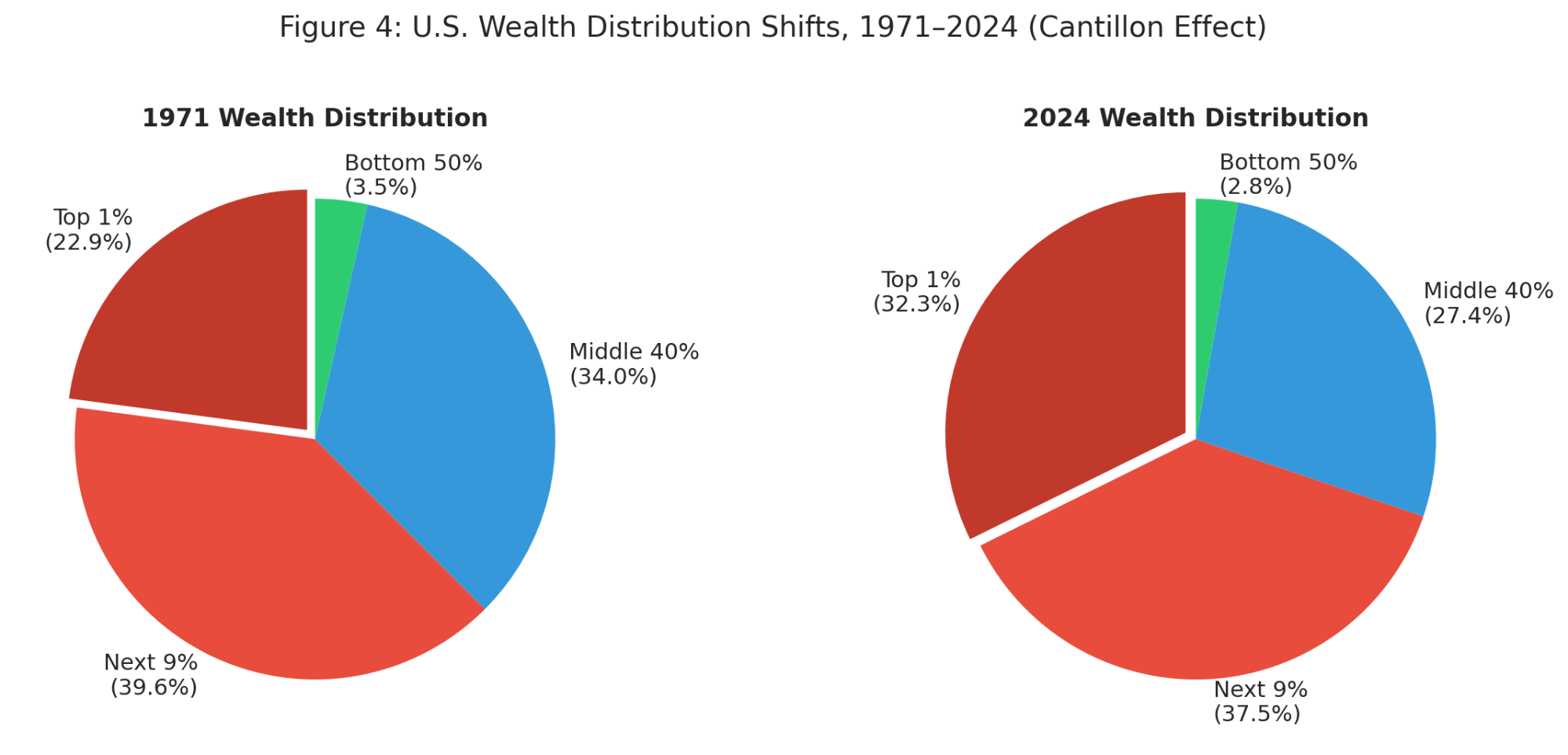

The eighteenth-century economist Richard Cantillon first described what is now known as the 'Cantillon Effect': the observation that monetary expansion does not affect all economic actors equally or simultaneously.[22] Those who receive newly created money first—typically banks, financial institutions, and government contractors—can spend it before prices have adjusted upward. By the time the money reaches ordinary workers and savers, prices have already risen, reducing their purchasing power.

This insight has profound implications for understanding the distributional consequences of fiat money. Monetary expansion functions as a mechanism of wealth transfer from later recipients of new money to earlier recipients. In contemporary terms, this means a systematic transfer from wage earners to asset holders, from Main Street to Wall Street, from the young to the old.[1]

Empirical Evidence of Wealth Concentration

The empirical record strongly supports the Cantillon thesis. Since 1971, wealth inequality has increased substantially across developed economies. In the United States, the share of wealth held by the top 1% has risen from approximately 23% in 1971 to over 32% today, according to Federal Reserve Distributional Financial Accounts. Meanwhile, the bottom 50% of Americans hold less than 3% of total wealth, with median real wages stagnating for decades.[23]

Wealth Cohort | 1971 Share | 2024 Share | Change (pp) |

Top 0.1% | 7.2% | 13.8% | +6.6 |

Top 1% | 22.9% | 32.3% | +9.4 |

Top 10% | 62.5% | 69.8% | +7.3 |

Middle 40% | 34.0% | 27.4% | -6.6 |

Bottom 50% | 3.5% | 2.8% | -0.7 |

Sources: Federal Reserve Distributional Financial Accounts, World Inequality Database[23][24]

The correlation between monetary expansion and wealth concentration is not coincidental. When central banks engage in quantitative easing—purchasing financial assets with newly created money—they directly inflate asset prices. Those who already own assets (primarily the wealthy) see their net worth increase, while those who do not (primarily wage earners) experience rising living costs without corresponding increases in wealth or income.[25]

The Ethical Dimension: Monetary Debasement and Human Dignity

The entrepreneur Jack Mallers, in a 2023 address to the Bitcoin Policy Institute, articulated this dynamic with pointed clarity: 'Printing money is an affront to human dignity.'[26] This framing—though it may seem rhetorical—captures an essential ethical truth. Money represents a claim arising from the contribution of value to others. When an individual works, they enter into an implicit contract with society: they sacrifice their time and energy today in exchange for the ability to claim equivalent value tomorrow. When governments and central banks expand the money supply at will, they break that implicit promise.

The thermodynamic framework developed above deepens this ethical critique. When a worker expends energy to create value, they are participating in the universe's fundamental process of creating order against entropy. Their labor is not merely economic activity—it is a local decrease in entropy, purchased at the cost of their finite time and energy. Money is supposed to preserve this achievement. When money is created without corresponding energy expenditure, it dilutes the genuine order that workers have created. The thermodynamic perspective thus reframes monetary debasement not merely as an economic policy with distributional consequences, but as a fundamental violation of the relationship between effort and reward.

The philosopher Robert Nozick argued in Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974) that taxation of earnings from labor is equivalent to forced labor. If the state takes 30% of your income, it is as if you are compelled to work 30% of your time for the state.[27] Inflation extends this logic: it functions as a concealed form of expropriation that operates through the debasement of savings rather than the direct extraction of income. The worker who saves for 30 years finds a substantial portion of their accumulated labor eroded, not through visible taxation, but through the invisible decline of purchasing power.

Civilizational Consequences: Time Preference and Social Indicators

The effects of monetary debasement may extend beyond individual welfare to civilizational trajectory. Economists of the Austrian tradition have long emphasized the concept of time preference—the degree to which individuals value present satisfaction over future satisfaction. A society with low time preference defers gratification, invests in the future, and builds institutions designed to outlast their founders. A society with high time preference consumes in the present, neglects maintenance and investment, and may experience gradual civilizational decline.[28]

Monetary systems shape incentives that influence time preference. When money holds its value, individuals are incentivized to save, to invest, to build for the future. When money loses value, the incentive structure shifts: consume now, before your purchasing power erodes. Borrow rather than save. Speculate rather than invest. The time horizon contracts from generations to quarters.[1]

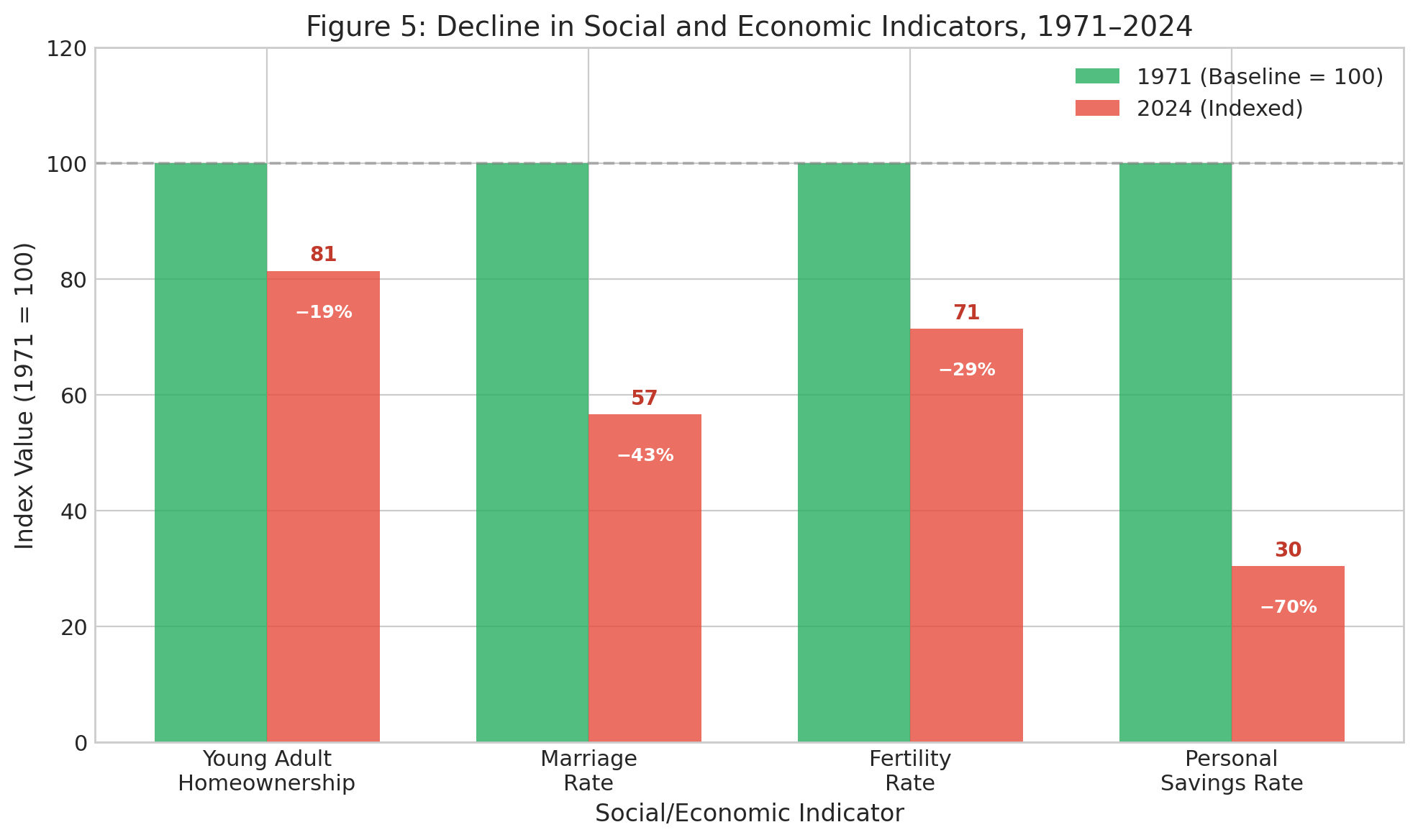

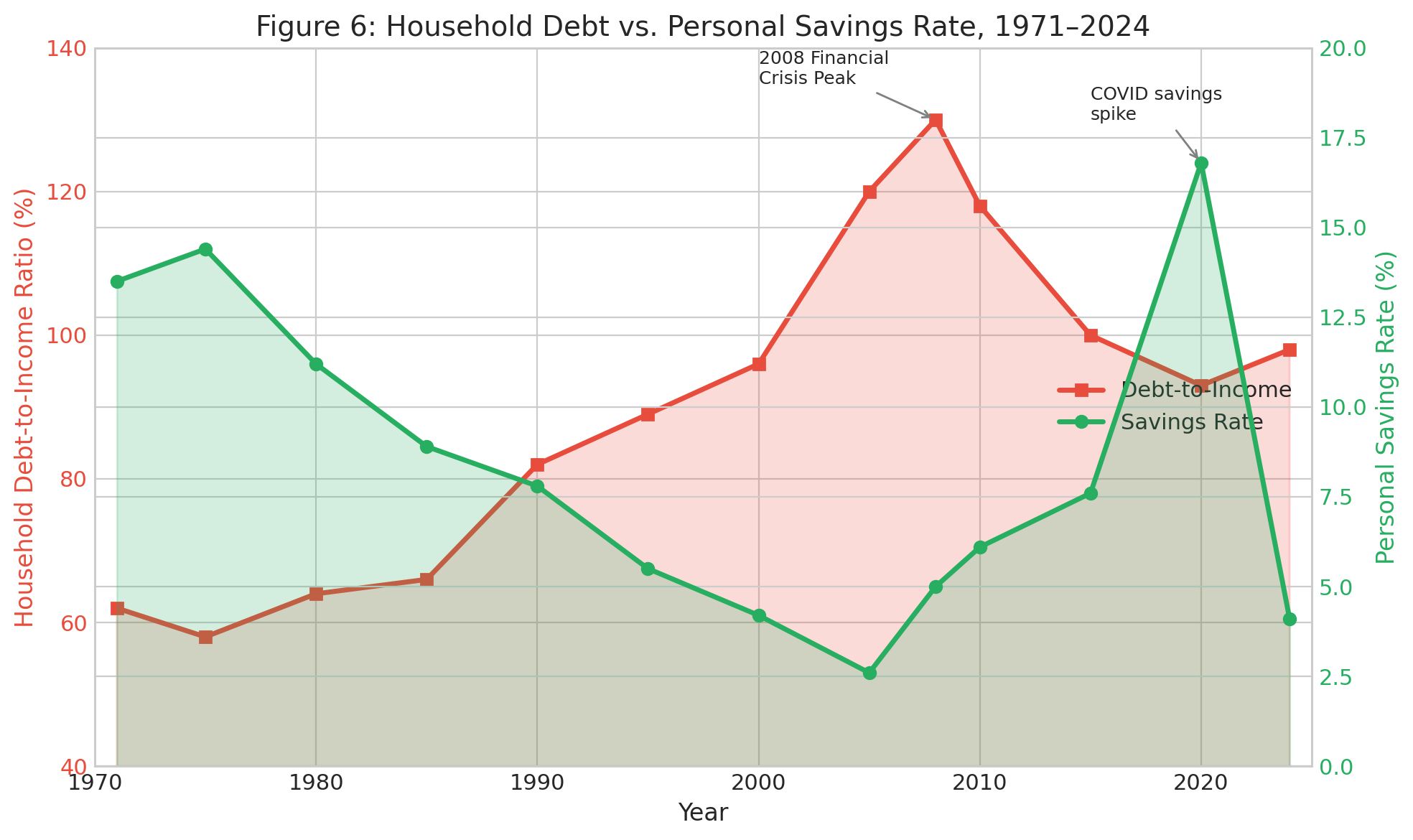

Indicator | 1971 | 2024 | Direction |

Homeownership Rate (Ages 25-34) | 47.3% | 38.5% | ↓ |

Marriage Rate (per 1,000) | 10.6 | 6.0 | ↓ |

Fertility Rate (births per woman) | 2.27 | 1.62 | ↓ |

Personal Savings Rate | 13.5% | 4.1% | ↓ |

Household Debt-to-Income Ratio | 62% | 98% | ↑ |

Infrastructure Quality Grade (ASCE) | N/A | C- | — |

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, BLS, CDC, ASCE Report Card for America's Infrastructure[29][17][30][31]

The correlations presented in Table 5 and Figures 5-6 are suggestive but do not establish definitive causation. Since the end of the Bretton Woods system, the United States has witnessed declines in family formation, homeownership rates among young adults, fertility, and savings behavior, alongside increases in household debt. While these correlations are consistent with the hypothesis that monetary instability elevates time preference—making long-term commitments like marriage, children, and homeownership increasingly difficult for median-income households—alternative explanations warrant consideration. Cultural shifts, technological changes, policy factors beyond monetary regime, and demographic transitions all contribute to these trends. The temporal alignment with the post-1971 monetary regime is striking, but disentangling these factors requires further research.[28]

Bitcoin as Exit: Sound Money for the Digital Age

Against this backdrop, Bitcoin emerges not merely as a speculative asset or technological curiosity, but as a potential solution to the fundamental problem of preserving value across time. Bitcoin's fixed supply of 21 million coins, enforced by cryptographic consensus rather than political discretion, represents the first purely digital instantiation of absolute scarcity.[10]

The economist Albert Hirschman, in his seminal work Exit, Voice, and Loyalty (1970), distinguished between two responses to organizational decline: voice (attempting to reform the institution from within) and exit (leaving for an alternative).[32] For decades, monetary reformers have attempted voice—advocating for sound money policies, balanced budgets, and return to commodity standards. These efforts have largely failed. Central bank balance sheets have only expanded; debt levels have only increased; purchasing power has only declined.

Bitcoin offers exit. For the first time in human history, there exists a parallel financial system—a monetary network that does not require government acceptance or central bank participation. Individuals can opt out of fiat currency and store their savings in a system designed to preserve rather than erode purchasing power. When voice is no longer effective, exit becomes a powerful alternative.[1]

The thermodynamic framework developed in this chapter reveals why Bitcoin's proof-of-work is not a limitation but its essential feature. In an age of infinite digital replication, where artificial intelligence can generate unlimited synthetic content at near-zero marginal cost, how does one establish genuine value? The answer is the same as it has always been: through irreversible energy expenditure. Bitcoin mining is the explicit, measurable conversion of energy into monetary order—the creation of what we have termed crystallized intelligence that can be verified, stored, and transferred, but never counterfeited or inflated.[11]

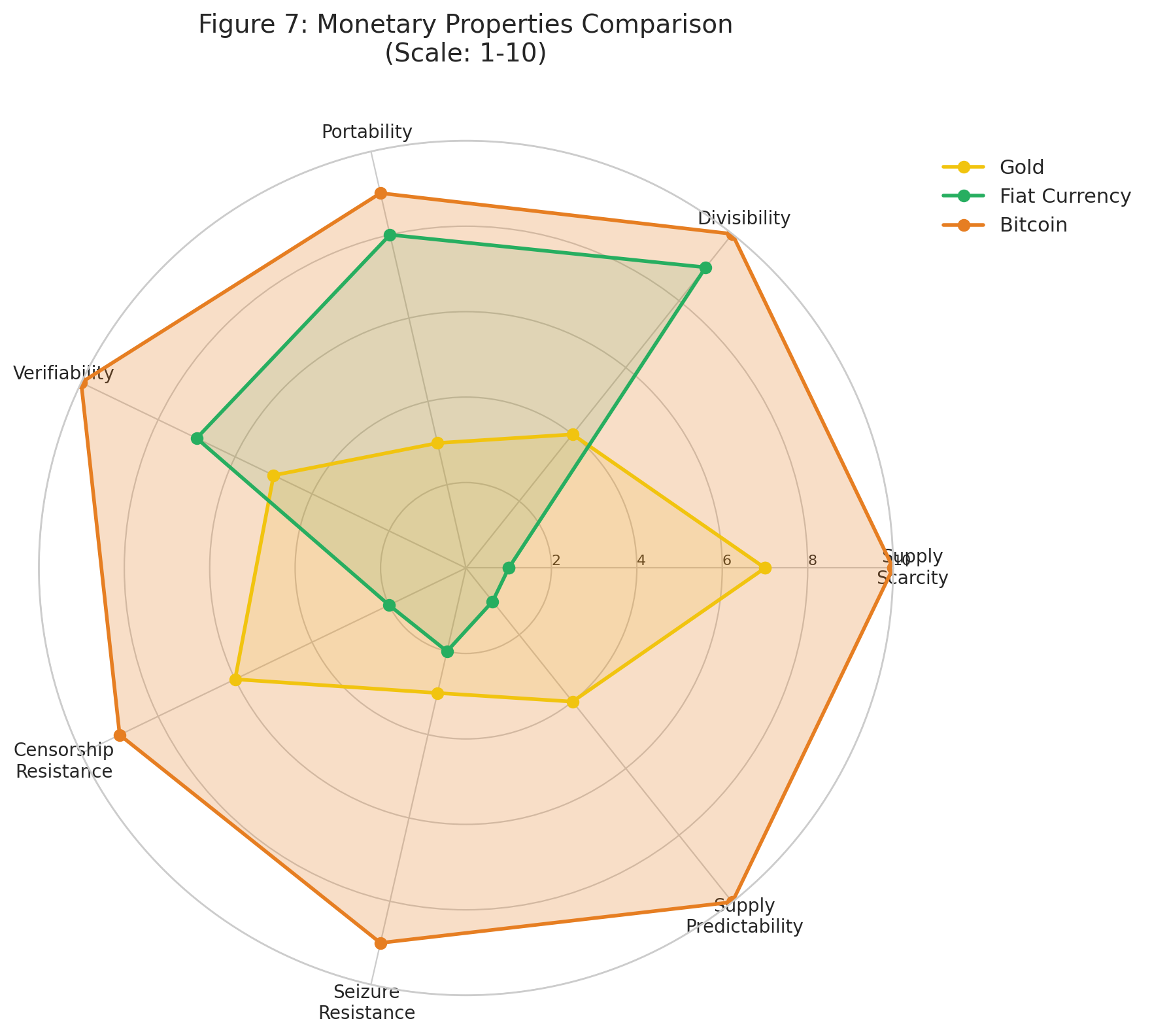

Table 6: Monetary Properties Comparison

Property | Gold | Fiat Currency | Bitcoin |

Supply Cap | Unfixed (~1.5%/yr) | Unlimited | 21 million |

Thermodynamic Anchor | Mining energy | None | Proof-of-work |

Divisibility | Physical limits | High | 100M satoshis |

Portability | Low (physical) | High (digital) | High (digital) |

Verification | Requires expertise | Trusted third party | Cryptographic |

Censorship Resistance | Moderate | Low | High |

Supply Predictability | Low (mining) | None (discretionary) | Perfect (algorithmic) |

Source: Author's analysis based on Ammous (2018) and Saylor (2024)[1][33]

The properties enumerated in Table 6 and visualized in Figure 7 illustrate why Bitcoin represents a meaningful alternative to existing monetary options. Note the inclusion of 'Thermodynamic Anchor' as a key property. Gold, while historically sound, has a relatively weak anchor—new gold can always be mined if the price rises sufficiently. Fiat currency has no thermodynamic anchor at all. Bitcoin uniquely combines absolute supply scarcity with continuous, verifiable energy expenditure, creating arguably the strongest thermodynamic anchor ever achieved in a monetary system.[1]

Counterarguments and Limitations

Intellectual honesty requires acknowledging significant counterarguments to the thesis presented in this chapter. First, mainstream economists argue that moderate inflation serves legitimate purposes: it lubricates labor markets by enabling real wage adjustments, provides central banks with policy flexibility during recessions, and reduces the real burden of debt for households and governments. The deflationary alternative, they contend, risks debt-deflation spirals and economic stagnation.

Second, Bitcoin's utility as a store of value remains constrained by significant volatility. While long-term holders have generally seen purchasing power appreciation, short-term volatility of 50% or more within a single year challenges Bitcoin's use as a reliable savings vehicle for those with near-term spending needs. The asset's fifteen-year track record, while impressive, is brief compared to gold's millennia or even fiat currency's half-century since Bretton Woods.

Third, environmental concerns about proof-of-work energy consumption—while addressed by the thermodynamic framework presented here—remain politically salient and may influence regulatory responses. Fourth, regulatory uncertainty, adoption barriers, and the technical complexity of self-custody present practical obstacles to Bitcoin's monetary function. These limitations do not invalidate the theoretical framework but contextualize its practical applicability.

Money as Crystallized Time and Energy

This chapter has argued that money, at its most fundamental level, represents human time and energy in abstracted form—or, in thermodynamic terms, the crystallization of intelligent effort into storable, transferable tokens. This understanding has profound implications for how we evaluate monetary systems.

Intelligence, as Mostaque observes, functions as the universe's engine for creating temporary pockets of order against entropy.[7] Money is one of humanity's most important tools for preserving and coordinating that order across time. Sound money maintains the connection between monetary tokens and the energy expenditure required to create genuine order. Fiat money severs that connection, creating the illusion of order while actually facilitating entropy—the gradual dissolution of value, savings, and civilizational time horizons.

The empirical record demonstrates that fiat currency has performed poorly as a store of value. Since 1971, the U.S. dollar has lost approximately 87% of its purchasing power as measured by CPI-U.[16] Workers must labor significantly longer to afford housing, education, and healthcare.[20] Wealth has concentrated among those who hold financial assets and receive newly created money first.[23] Social indicators suggest patterns consistent with rising time preference—declining savings, increasing debt, reduced family formation—though the causal relationships require further investigation.[28]

Bitcoin offers an alternative grounded in thermodynamic reality. Its proof-of-work mechanism is not wasteful—it is the essential process of converting energy into monetary order. Every bitcoin represents verified, irreversible conversion of physical energy into informational scarcity. This energy expenditure is not a cost to be minimized but the feature that gives Bitcoin meaning in an age of infinite digital replication.[11]

The scarce resource is credible time. Money, properly conceived, is how we measure and preserve it. Bitcoin, for the first time in the digital age, provides a measuring stick that does not shrink—a crystallization of energy that preserves the order human beings create against the entropy that would otherwise dissolve it. Whether Bitcoin achieves widespread monetary adoption remains uncertain; what seems clear is that it represents a genuinely novel approach to an ancient problem.[33]

References

[1] Ammous, S. (2018). The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking. Wiley.

[2] Smith, A. (1776). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. W. Strahan and T. Cadell.

[3] Ricardo, D. (1817). On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. John Murray.

[4] Jevons, W. S. (1871). The Theory of Political Economy. Macmillan. See also Menger, C. (1871). Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftslehre.

[5] Menger, C. (1892). 'On the Origin of Money.' Economic Journal, 2(6), 239-255.

[6] Mises, L. von. (1912). The Theory of Money and Credit. Yale University Press.

[7] Mostaque, E. (2024). 'Intelligence as Entropy Reduction.' Remarks at AI Safety Summit, Seoul, May 2024. The formulation draws on Friston, K. (2010). 'The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory?' Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127-138.

[8] Schrödinger, E. (1944). What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell. Cambridge University Press.

[9] England, J. (2013). 'Statistical Physics of Self-Replication.' Journal of Chemical Physics, 139(12), 121923. See also Georgescu-Roegen, N. (1971). The Entropy Law and the Economic Process. Harvard University Press.

[10] Nakamoto, S. (2008). 'Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.' Bitcoin.org.

[11] Lowery, J. (2023). Softwar: A Novel Theory on Power Projection and the National Strategic Significance of Bitcoin. MIT Master's Thesis.

[12] Szabo, N. (2005). 'Bit Gold.' Unenumerated Blog, December 2005.

[13] Antonopoulos, A. (2017). Mastering Bitcoin: Programming the Open Blockchain. O'Reilly Media.

[14] Nixon, R. M. (1971). Address to the Nation Outlining a New Economic Policy, August 15, 1971. American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-the-nation-outlining-new-economic-policy-the-challenge-peace

[15] Eichengreen, B. (2011). Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar. Oxford University Press.

[16] Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. (2024). Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED). https://fred.stlouisfed.org

[17] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024). Consumer Price Index Historical Data. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/

[18] International Monetary Fund. (2024). Global Debt Database. IMF.

[19] Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. (2024). Consumer Price Index (Estimate) 1800–Present.

[20] National Association of Realtors. (2024). Housing Affordability Index. NAR Research.

[21] College Board. (2024). Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid 2024.

[22] Cantillon, R. (1755). Essai sur la Nature du Commerce en Général. Institut National d'Études Démographiques.

[23] Federal Reserve Board. (2024). Distributional Financial Accounts. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

[24] Saez, E. & Zucman, G. (2016). Wealth Inequality in the United States Since 1913. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(2), 519-578.

[25] Congressional Research Service. (2023). Federal Reserve: Balance Sheet Reduction. Report IF12147.

[26] Mallers, J. (2023). 'The Moral Case for Bitcoin.' Address to Bitcoin Policy Institute Annual Conference, Washington, D.C., October 2023.

[27] Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Basic Books.

[28] Hoppe, H.-H. (2001). Democracy: The God That Failed. Transaction Publishers.

[29] U.S. Census Bureau. (2024). Housing Vacancies and Homeownership. Current Population Survey.

[30] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). National Vital Statistics System. CDC.

[31] American Society of Civil Engineers. (2021). 2021 Report Card for America's Infrastructure. ASCE.

[32] Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Harvard University Press.

[33] Saylor, M. (2024). 'Bitcoin and Digital Capital.' Keynote Address, MicroStrategy World Conference, Las Vegas, May 2024. See also Saylor, M. (2020). Interview with Real Vision Finance, August 2020.

Page

Coming Soon

This chapter will be available soon.