Part 3: TRANSFORMATION · Chapter 9

Technological Deflation

The Structural Paradox

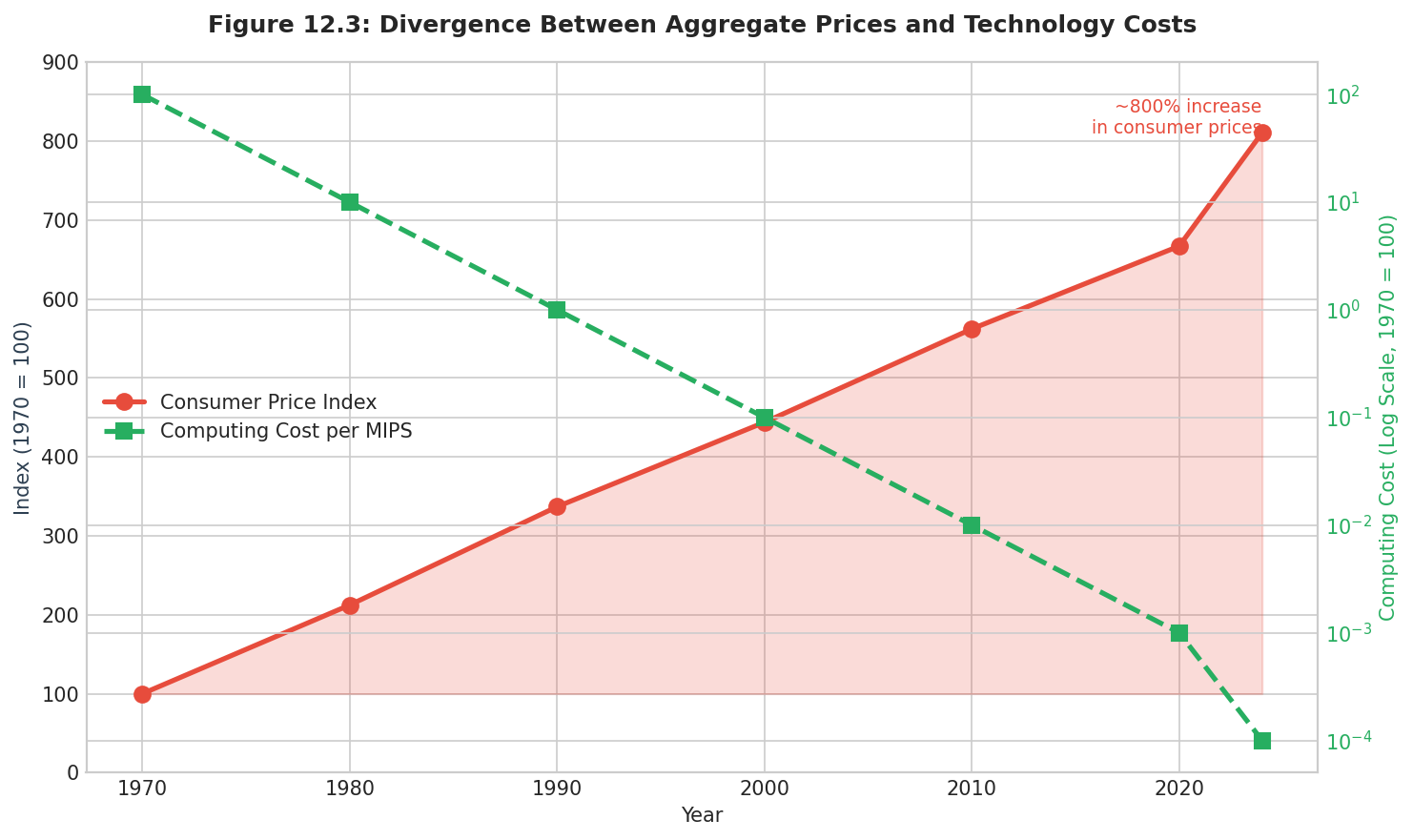

Classical economic theory establishes that, under conditions of perfect competition, markets drive prices toward marginal production costs over time [9.1]. Sustained technological improvement should therefore manifest as declining prices—a phenomenon termed "technological deflation" [9.2]. Yet despite unprecedented productivity gains, aggregate price levels in developed economies have risen persistently. The U.S. Consumer Price Index increased approximately 800% between 1970 and 2024, even as computing costs declined by approximately twelve orders of magnitude [9.3].

Understanding this divergence requires examining not merely policy choices but the structural foundations of contemporary monetary systems. This chapter argues that the gap between technological capability and price-level reality reflects structural incompatibility between debt-based monetary systems and technological deflation. The core insight, articulated by Mostaque in his analysis of monetary-technological dynamics, holds that fiat currency systems are inherently debt-based, requiring perpetual nominal growth to service compounding interest obligations [9.4]. This structural feature reveals why policy adjustments within the existing monetary framework cannot resolve the tension between AI-driven productivity and monetary architecture—the system's survival depends on preventing precisely what technology promises to deliver.

Theoretical Foundations of Technological Deflation

Marshall's principles established that, under conditions of perfect competition, long-run equilibrium price equals the minimum point of the long-run average cost curve [9.1]. Schumpeter enriched this framework through "creative destruction," wherein innovation generates productivity gains that ultimately benefit consumers as temporary monopoly profits are competed away [9.5]. Historical evidence supports this theoretical expectation: between 1870 and 1900, wholesale prices in the United States fell approximately 30% while real GDP nearly tripled under the gold standard [9.6, 9.7].

Importantly, research has distinguished between different types of deflation with markedly different economic consequences. Borio and colleagues at the Bank for International Settlements distinguished between "good" productivity deflation and "bad" debt deflation, finding that only the latter correlates with economic distress [9.8]. Atkeson and Kehoe examined 100 years of data across 17 countries and found no consistent relationship between deflation and depression [9.9]. Selgin argued that productivity-driven deflation is not only benign but optimal, distributing technological gains broadly through increased purchasing power [9.10].

Table 9.1: Historical Episodes of Productivity-Driven Deflation

Period | Region | Annual Deflation | Annual Real GDP Growth | Primary Driver |

1870-1896 | United States | -1.5% | +4.5% | Industrialization |

1920-1929 | United States | -1.0% | +4.2% | Electrification |

1995-2024 | Computing sector | -15 to -25% | Varies by application | Moore's Law |

2010-2024 | Solar energy | -12% | Sector-specific growth | Manufacturing scale |

Sources: [9.2], [9.3], [9.11]

Artificial Intelligence as Unprecedented Deflationary Force

Previous technological revolutions automated physical tasks or routine information processing. Artificial intelligence automates cognitive work—the capability that has historically commanded premium wages due to its non-routine character [9.12]. Acemoglu and Restrepo suggest that AI may disproportionately favor displacement over reinstatement by automating tasks across a much broader range of cognitive complexity than previous technologies [9.13].

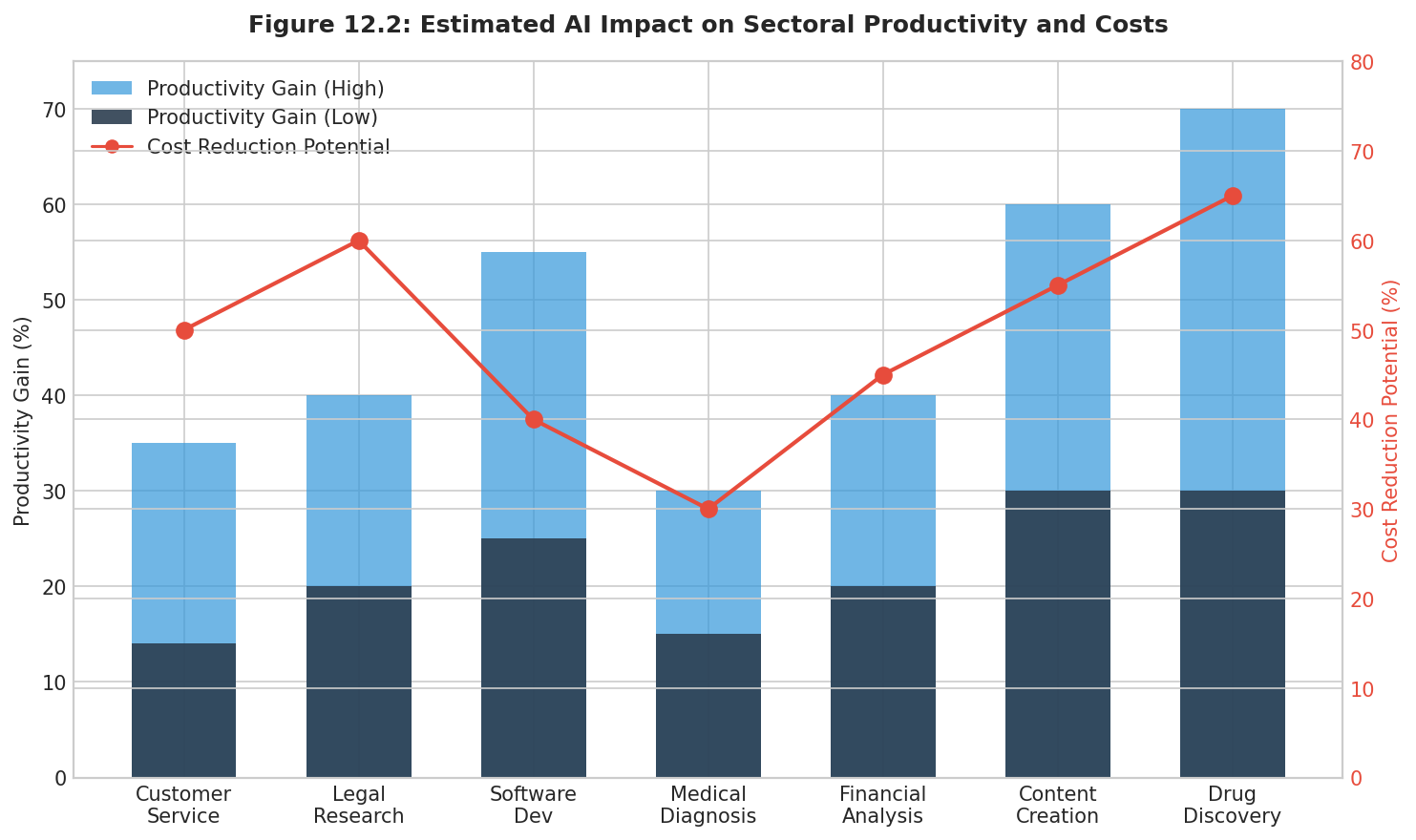

Empirical evidence documents significant deflationary potential: Brynjolfsson and colleagues found 14% productivity gains among customer service agents using AI [9.14]; Noy and Zhang documented 40% reduction in writing task completion time [9.15]; Peng and colleagues reported 25-55% productivity improvements in software development [9.16]. Agrawal, Gans, and Goldfarb conceptualize AI as dramatically reducing the cost of prediction—a fundamental input to most economic decisions [9.17].

Rifkin's "zero marginal cost" phenomenon extends to cognitive services: once developed, AI models serve millions with only incremental infrastructure expense [9.18]. When marginal costs approach zero, competitive pressure drives prices toward zero absent artificial scarcity mechanisms. The distribution of this surplus—whether to consumers through lower prices or to capital owners through higher profits—depends critically on monetary architecture, as the following sections demonstrate.

The Structural Incompatibility Thesis

The central argument of this chapter is that debt-based fiat money is structurally incompatible with sustained technological deflation—not merely in tension with it, but fundamentally unable to accommodate it over extended periods. This incompatibility operates through three interconnected mechanisms that reveal why policy adjustment within the existing framework cannot resolve the fundamental contradiction.

Mechanism One: Deflation Increases Real Debt Burden

Modern monetary systems create money primarily through bank lending—what Werner terms "credit creation" [9.19]. When banks extend loans, they create deposits; repayment destroys money. This system functions smoothly only when new credit creation exceeds repayments. Deflation poses a significant structural threat: when prices fall, the real value of debt increases, making repayment more burdensome. Fisher's debt-deflation theory demonstrates how this dynamic can trigger cascading defaults [9.20].

Consider a business that borrows $1 million at 5% interest to fund operations. Under 2% inflation, the real interest rate is 3%, and revenue growth helps service debt. Under 5% deflation—a rate Booth [9.21] considers plausible given current technological trajectories, though estimates vary considerably—the real interest rate becomes 10%, while revenues decline in nominal terms. The real debt burden approximately doubles over seven years if only interest is serviced, with principal remaining outstanding. Multiply this across an economy where total debt exceeds 350% of GDP [9.22], and deflation becomes systemically destabilizing.

Mechanism Two: The Distributional Consequences of Inflation Targeting

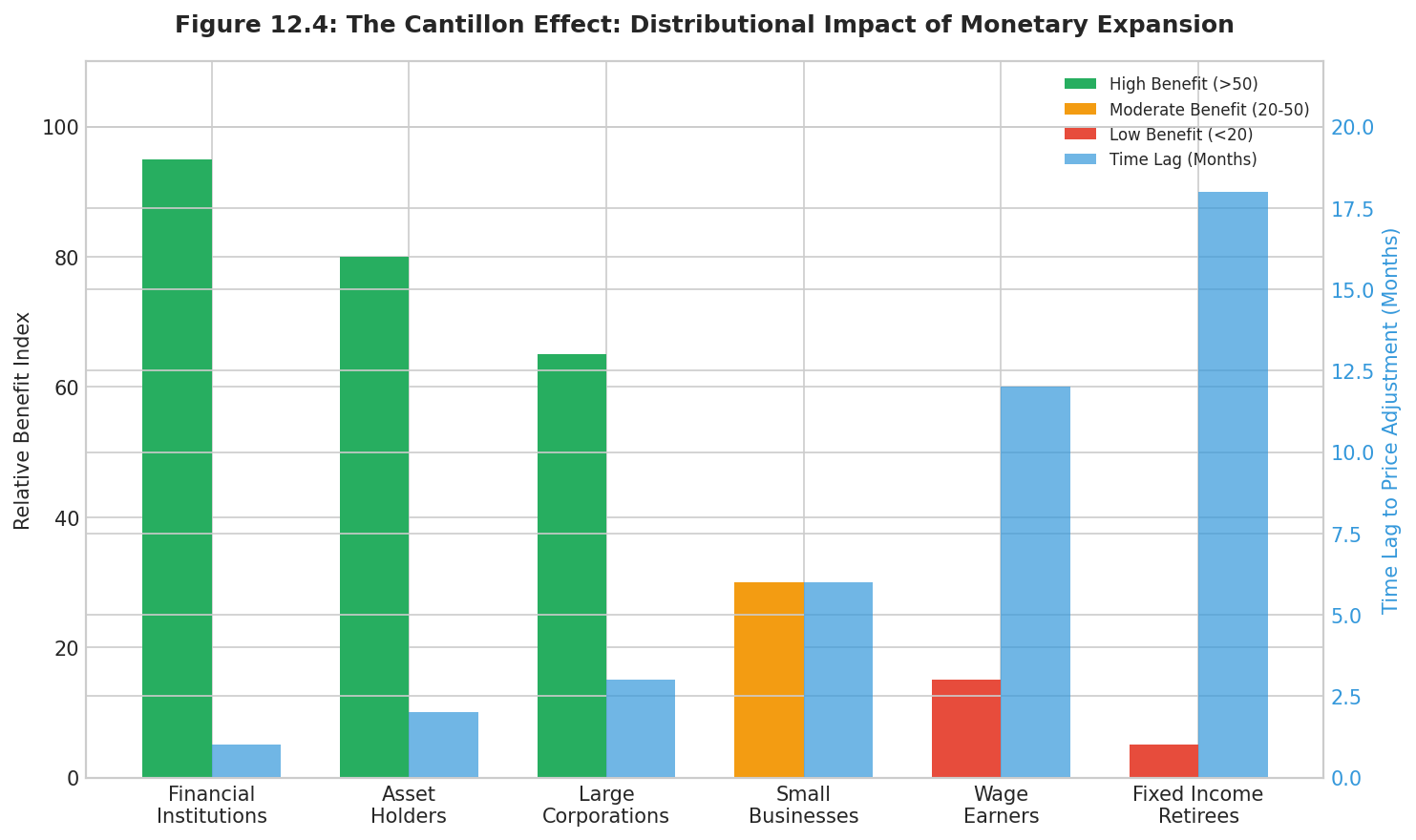

Recognizing deflation's threat to the credit system, central banks have adopted inflation targeting as their primary mandate. The explicit goal of 2% annual inflation [9.23] represents policy that systematically reduces purchasing power to prevent natural deflation from manifesting. Bernanke articulated the Federal Reserve's commitment to avoiding deflation through aggressive monetary policy, including "unconventional measures if necessary" [9.24].

This policy stance creates distributional effects first identified by Cantillon in the 18th century: monetary expansion benefits those who receive new money first (financial institutions, asset holders) before prices adjust. Coibion and colleagues documented empirically that monetary policy loosening increases income inequality with effects persisting for years [9.25]. Domanski and colleagues found that quantitative easing significantly increased wealth inequality through asset price appreciation [9.26]. The system thus produces continuous wealth transfer from savers to debtors, from workers to capital holders, from future to present consumption.

Mechanism Three: The System Requires Perpetual Growth

The deepest incompatibility emerges from examining what interest represents in a debt-based system. Interest payments require borrowers to return more money than was created through their loan. Across the system, this is possible only if the money supply continuously expands or if some borrowers default. While velocity and credit turnover partially offset this dynamic, the aggregate tendency toward debt accumulation remains evident in historical data showing persistent debt-to-GDP growth across developed economies [9.22]. The system thus requires perpetual nominal growth—not as policy choice but as structural necessity.

This structural feature explains why technological abundance fundamentally challenges the model. If AI drives marginal costs toward zero across expanding sectors, prices naturally fall. But falling prices mean falling nominal revenues, declining ability to service debt, and eroding justification for interest payments. The scarcity that justifies charging interest diminishes. A monetary system premised on scarcity cannot easily accommodate technology that produces abundance—not because policymakers choose poorly, but because the architecture requires scarcity's perpetuation.

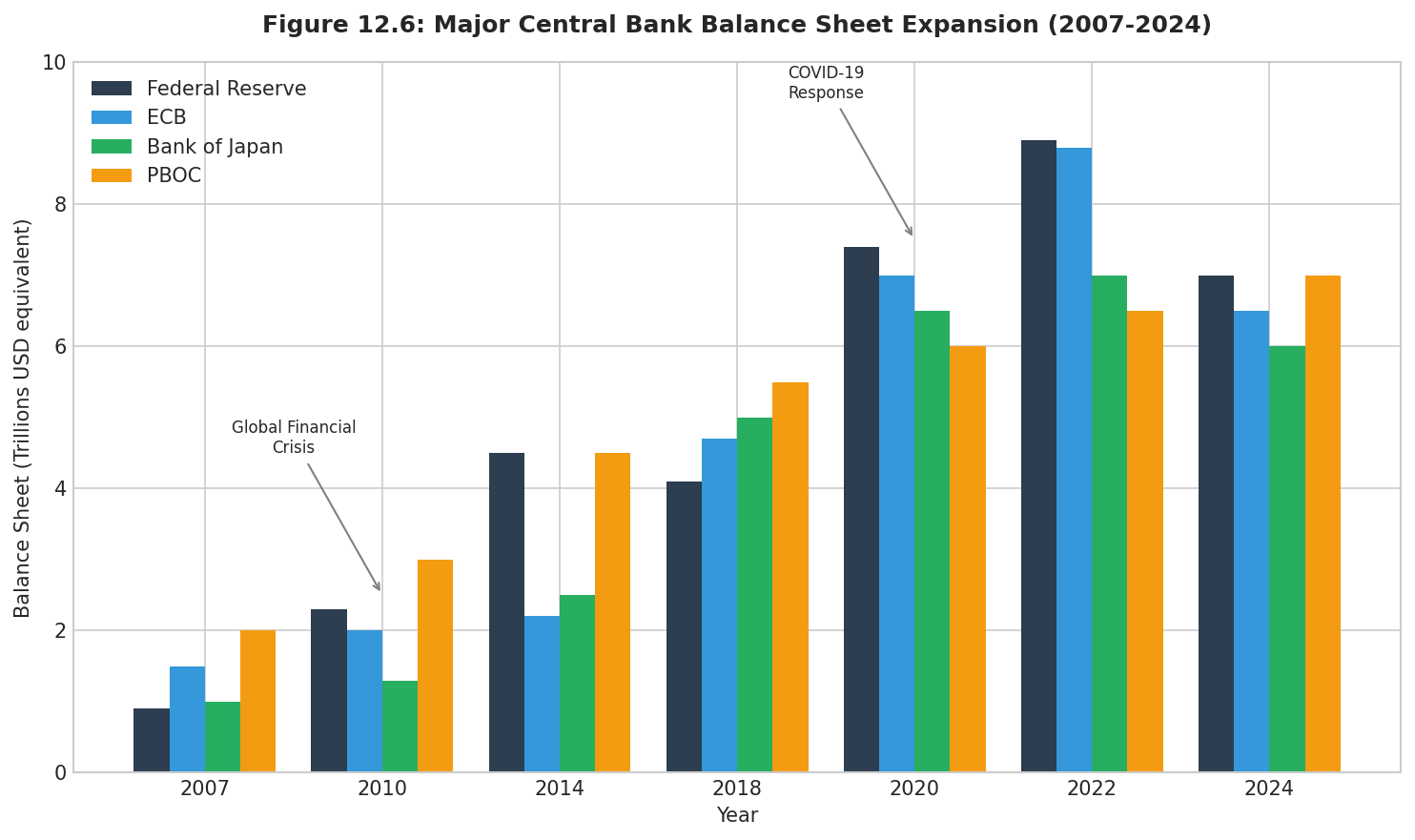

Minsky's "financial instability hypothesis" illuminates the endpoint: stability encourages risk-taking, increasing fragility until crisis requires intervention [9.27]. Each intervention—lower rates, quantitative easing, fiscal stimulus—resolves the immediate crisis while increasing debt levels and reducing policy space. Central bank balance sheets expanded from under $4 trillion globally to over $28 trillion since 2008 [9.28]; global debt now exceeds $315 trillion [9.22]. The system's survival requires ever-larger interventions to offset ever-stronger deflationary pressure.

Table 9.2: Structural Incompatibility Between Debt-Money and Technological Deflation

Debt-Based System Requirement | Technological Deflation Reality | Resulting Tension |

Nominal growth to service debt | Falling prices reduce nominal revenue | Rising real debt burden; default pressure |

Positive inflation to prevent debt spiral | Productivity gains should lower prices | Central banks must offset deflation |

Scarcity to justify interest payments | AI drives marginal costs toward zero | Abundance undermines credit rationale |

Perpetual monetary expansion | Fixed real value of goods/services | Asset inflation absorbs productivity gains |

Savings discouraged by negative real rates | Falling prices should reward savers | Rational agents shift to consumption and speculation |

Source: Synthesized from [9.4], [9.19], [9.20], [9.27]

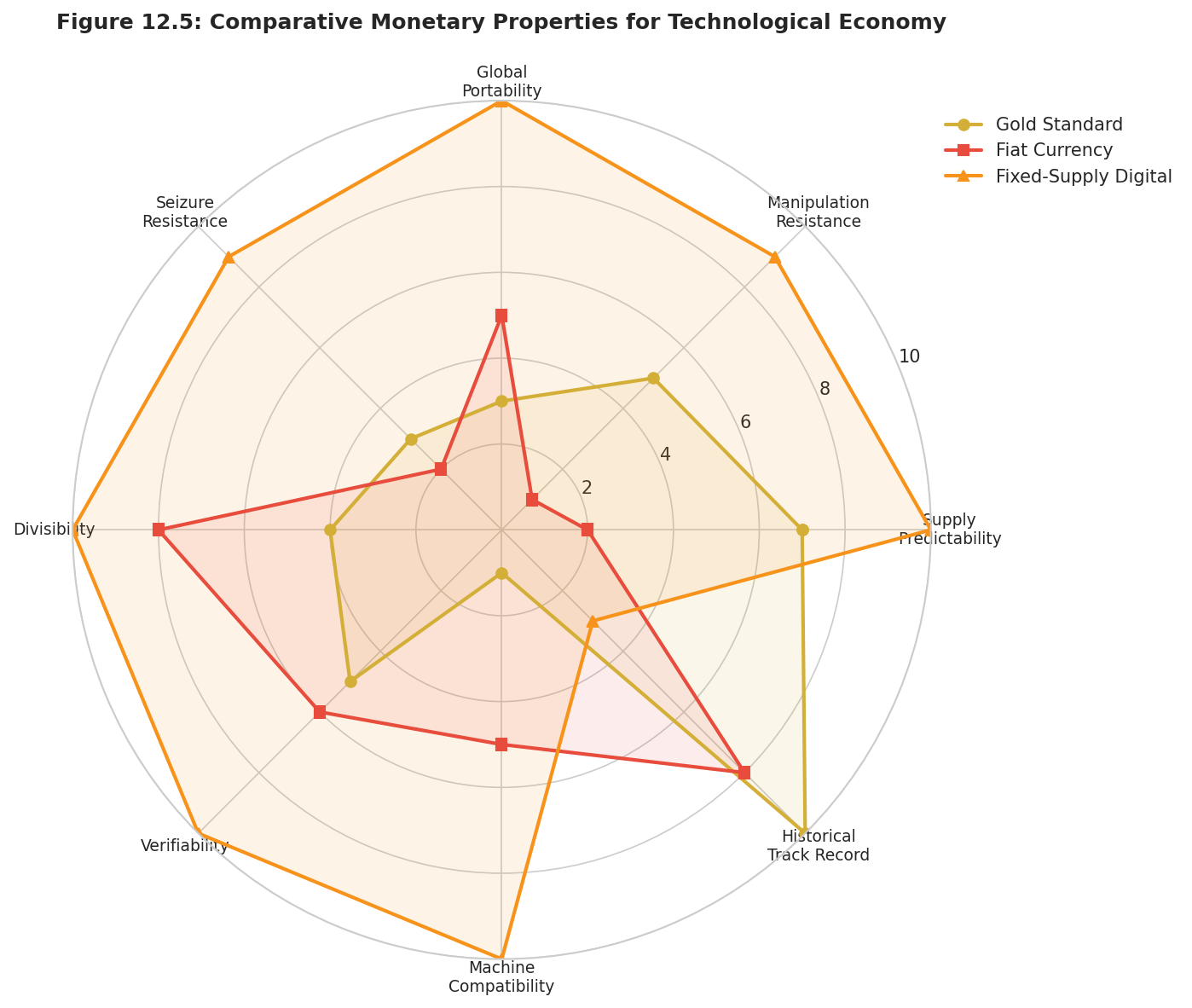

Bitcoin as Structural Resolution

If debt-based money is structurally incompatible with technological deflation by design, resolution requires monetary architecture change rather than policy adjustment. Bitcoin, introduced in 2009 [9.29], represents precisely such architectural change—a monetary system that resolves each structural incompatibility through fundamentally different design principles.

Fixed Supply Accommodates Deflation Naturally

Bitcoin's supply follows a predetermined algorithm approaching 21 million units [9.29]—fixed absolutely, not subject to policy discretion. Under this framework, technological deflation manifests exactly as classical theory predicts: as productivity increases, prices fall, and purchasing power rises. Holders of monetary units benefit directly from technological progress without needing to invest, speculate, or accept counterparty risk.

Athey and colleagues modeled this dynamic, finding that fixed supply combined with increasing adoption necessarily produces appreciation [9.30]. Schilling and Uhlig examined Bitcoin-fiat coexistence, demonstrating stable equilibria under certain conditions [9.31]. The key insight: under fixed-supply money, deflation distributes productivity gains broadly through appreciation rather than concentrating them through asset inflation.

No Debt Creation at Protocol Level

Bitcoin is created through proof-of-work mining, not lending. No debt obligation accompanies monetary unit creation; no interest payments require perpetual growth; no structural necessity demands scarcity's preservation. The monetary base exists independent of credit markets, providing a foundation that does not require expansion to maintain stability.

This eliminates the core incompatibility. Abundance does not threaten system stability because no debt service requires nominal growth. Deflation does not cascade through balance sheets because the monetary unit is not simultaneously someone's liability. The system can accommodate significant productivity improvements without the structural crises inherent to debt-based money—precisely the flexibility an AI-abundant economy requires.

Savings Function Preserved Across Deflationary Environment

Under fiat systems, saving is penalized: inflation erodes purchasing power, forcing savers into risk assets merely to maintain wealth. Under Bitcoin's fixed supply, saving is rewarded: purchasing power increases as productivity improves, allowing wealth preservation without counterparty exposure. This restoration of money's savings function addresses one of the deepest distortions in contemporary economies.

The implications extend beyond narrowly economic considerations to encompass cultural and temporal orientations. As Ammous argues, sound money promotes low time preference—the willingness to defer consumption for future benefit [9.32]. Inflationary money promotes high time preference and present-orientation. An AI-abundant economy requires long-term thinking: patient capital formation, intergenerational investment, and deferred gratification. Only monetary architecture that rewards rather than punishes saving can support such orientation.

Table 9.3: How Bitcoin Resolves Structural Incompatibilities

Structural Problem | Fiat System Response | Bitcoin Resolution |

Deflation increases real debt burden | Inflate to reduce real debt value | No debt at protocol level; deflation is benign |

System requires perpetual growth | Expand credit continuously | Fixed supply; no growth requirement |

Savers penalized by inflation | Force savers into risk assets | Purchasing power appreciation rewards saving |

Productivity gains captured by capital | Asset price inflation absorbs gains | Falling prices distribute gains broadly |

Scarcity required to justify interest | Maintain artificial scarcity | Abundance compatible with fixed supply |

Source: Author analysis based on [9.29], [9.30], [9.31], [9.32]

Why System Change, Not Policy Adjustment

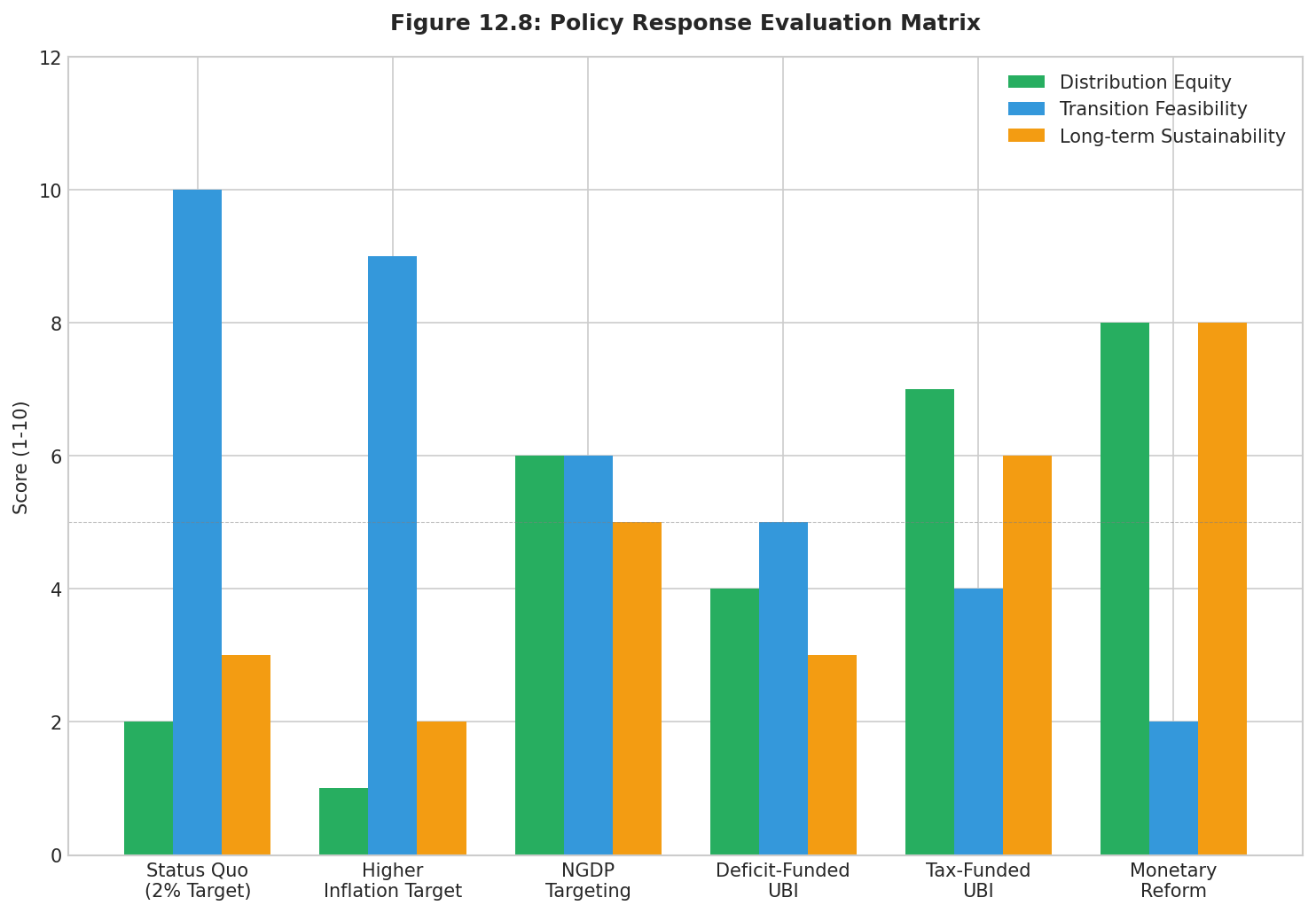

The analysis above explains why proposed policy adjustments within the fiat framework cannot resolve the fundamental tension. Consider the leading alternatives:

Higher inflation targets [9.33, 9.34]: This approach addresses symptoms while potentially exacerbating underlying imbalances, further eroding purchasing power while accelerating wealth concentration through asset inflation.

NGDP targeting [9.35, 9.36]: This framework would permit technological deflation when productivity rises, but existing debt structures assume inflation. Transition would trigger the debt-deflation dynamics the system was designed to prevent—not because the policy is wrong, but because the accumulated debt stock cannot survive what correct policy requires.

Universal Basic Income [9.37]: If funded through money creation, the Cantillon effect persists—asset prices inflate before transfers reach recipients. Only UBI funded through taxation genuinely redistributes, but this addresses distribution without resolving the structural incompatibility between debt-money and deflation.

Each policy operates within monetary architecture that structurally prevents technological deflation from benefiting consumers. The architecture itself must change. This represents not ideological preference but logical necessity: it is exceedingly difficult to accommodate abundance within a system that requires scarcity to function.

Challenges and Transition Considerations

Acknowledging the structural argument's validity does not resolve implementation challenges. This section addresses the principal objections and transition difficulties.

Addressing Standard Objections

The deflationary spiral objection holds that deflationary expectations become self-reinforcing: consumers delay purchases expecting lower future prices, reducing demand, causing further price declines. This objection conflates demand-collapse deflation (the 1930s) with productivity deflation (the late 19th century). Under productivity deflation, real incomes rise alongside falling prices, sustaining demand. The historical record of robust growth during the 1870-1896 period demonstrates that deflation per se does not preclude economic expansion [9.6].

The credit market objection asks how credit markets would function under a Bitcoin standard. This chapter's argument concerns money creation at the base layer, not the elimination of credit. Credit markets can function on a fixed-supply monetary base—as they did under the gold standard—with interest rates reflecting genuine time preference rather than inflation compensation. What changes is that credit cannot create new base money, constraining but not eliminating lending.

The volatility objection notes Bitcoin's price instability relative to established currencies. This reflects adoption-phase dynamics rather than inherent properties; volatility has declined as market capitalization and liquidity have increased. More fundamentally, fiat "stability" masks gradual purchasing power erosion—stability in nominal terms, instability in real terms.

Transition Challenges

Existing debt contracts denominated in fiat currencies assume continued inflation; rapid monetary transition would devastate debtors while rewarding those positioned in alternative assets—itself a distributional injustice. The political economy presents formidable obstacles, as beneficiaries of current arrangements wield disproportionate influence.

Bitcoin's scalability constraints currently limit its utility as a primary medium of exchange, though Layer 2 solutions such as the Lightning Network address transaction throughput. Workers displaced by AI require time and resources regardless of monetary framework; technological unemployment creates real hardship that monetary reform alone cannot address.

However, these are transition problems, not fundamental objections to the destination. Historical monetary transitions—from bimetallism to gold standard, from gold standard to Bretton Woods, from Bretton Woods to fiat—each involved disruption and distributional conflict. The question is whether the destination is correct, not whether the journey is comfortable. If debt-based money truly cannot accommodate AI-driven abundance, then transition costs must be weighed against the ongoing costs of forcing abundance through a scarcity-dependent system.

The Monetary Precondition for Abundance

This analysis has demonstrated that the tension between technological deflation and monetary policy is not incidental but structural. Fiat currency, created through debt and requiring perpetual nominal growth to service compounding interest, is fundamentally incompatible with the abundance that artificial intelligence promises to deliver. The three mechanisms of incompatibility—deflation increasing real debt burden, inflation targeting producing adverse distributional consequences, and the system requiring perpetual scarcity—explain why policy adjustment within the existing framework fails to resolve fundamental contradictions.

Bitcoin offers structural resolution: fixed supply accommodates deflation naturally, no debt creation at protocol level eliminates growth requirements, and preserved savings function rewards rather than punishes prudence. These are not incremental improvements but architectural alternatives to the debt-money paradigm.

The stakes are considerable. Artificial intelligence offers substantial potential improvements in human welfare—reduced costs, expanded access, potential liberation from routine cognitive labor. Whether this potential is realized depends on institutional frameworks that determine how productivity gains are distributed. The coming decades will require fundamental reconsideration of monetary arrangements taken for granted since 1971. The question is not whether technological deflation will occur—it already pervades technology-intensive sectors—but whether its benefits will flow broadly through lower prices and increased purchasing power, or narrowly through financial asset appreciation and concentrated wealth.

The transition to AI-driven abundance requires monetary system change—not policy adjustment. This is the monetary precondition for the technological future that innovation has made possible.

References

[9.1] Marshall, A. (1890). Principles of Economics. London: Macmillan.

[9.2] Bordo, M. D., & Filardo, A. J. (2005). Deflation in a Historical Perspective. BIS Working Papers, No. 186.

[9.3] Nordhaus, W. D. (2007). Two Centuries of Productivity Growth in Computing. Journal of Economic History, 67(1), 128-159.

[9.4] Mostaque, E. (2024). The Economic Implications of AI-Driven Deflation. Stability AI Policy Papers. Also: Keynote Address, AI Safety Summit, November 2024.

[9.5] Schumpeter, J. A. (1942). Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. New York: Harper & Brothers.

[9.6] Rothbard, M. N. (1963). America's Great Depression. Princeton: D. Van Nostrand.

[9.7] Friedman, M., & Schwartz, A. J. (1963). A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[9.8] Borio, C., Erdem, M., Filardo, A., & Hofmann, B. (2015). The Costs of Deflations: A Historical Perspective. BIS Quarterly Review, March, 31-54.

[9.9] Atkeson, A., & Kehoe, P. J. (2004). Deflation and Depression: Is There an Empirical Link? American Economic Review, 94(2), 99-103.

[9.10] Selgin, G. (1997). Less Than Zero: The Case for a Falling Price Level in a Growing Economy. London: Institute of Economic Affairs.

[9.11] IRENA. (2023). Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2022. Abu Dhabi: International Renewable Energy Agency.

[9.12] Autor, D. H. (2015). Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), 3-30.

[9.13] Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2018). The Race Between Man and Machine: Implications of Technology for Growth, Factor Shares, and Employment. American Economic Review, 108(6), 1488-1542.

[9.14] Brynjolfsson, E., Li, D., & Raymond, L. R. (2023). Generative AI at Work. NBER Working Paper, No. 31161.

[9.15] Noy, S., & Zhang, W. (2023). Experimental Evidence on the Productivity Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence. Science, 381(6654), 187-192.

[9.16] Peng, S., Kalliamvakou, E., Cihon, P., & Demirer, M. (2023). The Impact of AI on Developer Productivity: Evidence from GitHub Copilot. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2302.06590.

[9.17] Agrawal, A., Gans, J., & Goldfarb, A. (2018). Prediction Machines: The Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

[9.18] Rifkin, J. (2014). The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

[9.19] Werner, R. A. (2014). Can Banks Individually Create Money Out of Nothing? The Theories and the Empirical Evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis, 36, 1-19.

[9.20] Fisher, I. (1933). The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions. Econometrica, 1(4), 337-357.

[9.21] Booth, J. (2020). The Price of Tomorrow: Why Deflation is the Key to an Abundant Future. Vancouver: Stanley Press.

[9.22] Institute of International Finance. (2024). Global Debt Monitor, February 2024. Washington, DC: IIF.

[9.23] Bernanke, B. S., & Mishkin, F. S. (1997). Inflation Targeting: A New Framework for Monetary Policy? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 11(2), 97-116.

[9.24] Bernanke, B. (2002). Deflation: Making Sure It Doesn't Happen Here. Speech before the National Economists Club, Washington, D.C., November 21, 2002.

[9.25] Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y., Kueng, L., & Silvia, J. (2017). Innocent Bystanders? Monetary Policy and Inequality. Journal of Monetary Economics, 88, 70-89.

[9.26] Domanski, D., Scatigna, M., & Zabai, A. (2016). Wealth Inequality and Monetary Policy. BIS Quarterly Review, March, 45-64.

[9.27] Minsky, H. P. (1986). Stabilizing an Unstable Economy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

[9.28] Federal Reserve. (2024). Federal Reserve Statistical Release H.4.1: Factors Affecting Reserve Balances. Washington, DC: Board of Governors.

[9.29] Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. bitcoin.org.

[9.30] Athey, S., Parashkevov, I., Sarukkai, V., & Xia, J. (2016). Bitcoin Pricing, Adoption, and Usage: Theory and Evidence. Stanford GSB Research Paper, No. 16-42.

[9.31] Schilling, L., & Uhlig, H. (2019). Some Simple Bitcoin Economics. Journal of Monetary Economics, 106, 16-26.

[9.32] Ammous, S. (2018). The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

[9.33] Blanchard, O., Dell'Ariccia, G., & Mauro, P. (2010). Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 42(s1), 199-215.

[9.34] Ball, L. (2014). The Case for a Long-Run Inflation Target of Four Percent. IMF Working Paper, No. 14/92.

[9.35] Sumner, S. (2014). Nominal GDP Targeting: A Simple Rule to Improve Fed Performance. Cato Journal, 34(2), 315-337.

[9.36] Beckworth, D. (2019). Facts, Fears, and Functionality of NGDP Level Targeting. Mercatus Center Working Paper.

[9.37] Van Parijs, P., & Vanderborght, Y. (2017). Basic Income: A Radical Proposal for a Free Society and a Sane Economy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Coming Soon

This chapter will be available soon.